AUSSIES AT LE MANS: Part 2, The heroes

OUR journey through the history of Aussies at Le Mans continues, this time it’s on to some more recognisable names and remarkable stories from the 60s, 70s and 80s..

Read Part 1 of ‘Aussies at Le Mans’ here.

TONY GAZE

With Le Mans not contested during the years of World War II, it took another decade beyond peace for the third Australian to compete in the fabled 24 Hour, when in 1956 Tony Gaze made his debut on the Circuit La Sarthe.

Gaze is a legend of Australian Motorsport. Born in Melbourne in 1920, he flew Spitfires in the second world war for the Royal Air Force. His wartime service was extraordinary, receiving three DFCs – distinguished Flying Crosses – for his exploits in air combat, one of only 47 men to achieve that distinction. His career included 13.5 confirmed kills of enemy aircraft, but possibly more.

Gaze was shot down over Normandy in 1943, however with the help of the French Resistance was able to escape through Spain, returning to service in 1944.

Perhaps more famously than his World War Two exploits, Gaze is known as the man who suggested to the Duke of Richmond – Freddie March – that the access roads around RAF Westhampnett would serve as an ideal layout for a motor racing circuit.

From there, the Goodwood Circuit was born.

Gaze contested several races in the 1950s, finishing second in the Lady Wigram trophy and third in the 1954 New Zealand Grand Prix.

His sole Le Mans start came in 1956, driving a Frazer Nash Sebring with British driver Dickie Stoop. They completed 101 laps before an accident ended their race.

Gaze’s Le Mans story doesn’t end there, however, and uniquely it ties in with another Australian racing great – one who also attempted to conquer the French classic: Lex Davison.

Davison, the first four-time winner of the Australian Grand Prix, teamed with another famous name – Bib Stillwell – to tackle Le Mans in 1961 – the first time an all-Australian crew had competed in the race.

The pair had been invited to France by Essex Racing thanks mainly to their own exploits racing Aston Martins in Australia and New Zealand, primarily in the Australian Grand Prix and in the Australian Drivers’ Championship.

Sadly, a broken head gasket ended the day for their Aston Martin DB4 Zagato after only 25 laps.

That’s not the end of the story, however, and it’s here where the Gaze and Davison journeys become entwined.

Lex Davison was sadly killed in 1965 while practicing for a race at Sandown, in his native Melbourne. He left behind wife Diana and two sons, Jon and Richard.

Several years after Lex’s death, Diana married Tony Gaze to intrinsically link the histories and the futures of two great Australian racing families.

As well as becoming stepfather to Lex’s two sons, the marriage also ensured that Tony would later become a step-grandfather to Alex, Will and James Davison.

62-years after his grandfather raced at the iconic French track, Alex Davison made his Le Mans debut, driving a Gulf-backed Porsche 911 GTE with Ben Barker and Michael Wainwright.

It was a remarkable continuation of the story behind two of the great Australian racing families, intrinsically linked forever.

JACK BRABHAM

JACK ARTHUR BRABHAM was a Formula One driver, but much as it is with many of today’s F1 superstars, Brabham’s eye often strayed from pure open wheel competition to the challenges – both from a driving and engineering point of view – experienced only in long-distance endurance racing.

Sir Jack raced at Le Mans twice, both times before he had even claimed a single Formula One victory, let alone a World Championship

His first attempt came in 1957, finishing 15th outright driving a Coventry Climax-powered Cooper T39 with British driver Ian Raby.

He returned the following year, this time driving for the works Aston Martin squad with another future Sir – Stirling Moss – as his co-driver.

With Moss behind the wheel, Brabham’s Aston burst into the lead at the start of the race, pulling away at breakneck speed to have all bar three cars lapped just prior to their first scheduled pit stop.

However, just after 6pm, their race was over: A broken conrod left the car and Moss stranded at Mulsanne corner and Brabham didn’t even turn a lap.

That would be the end of Brabham’s Le Mans adventure – at least that of Brabham Senior. All three of his sons would later tackle the race, two of them achieving the ultimate prize. That story is still to come.

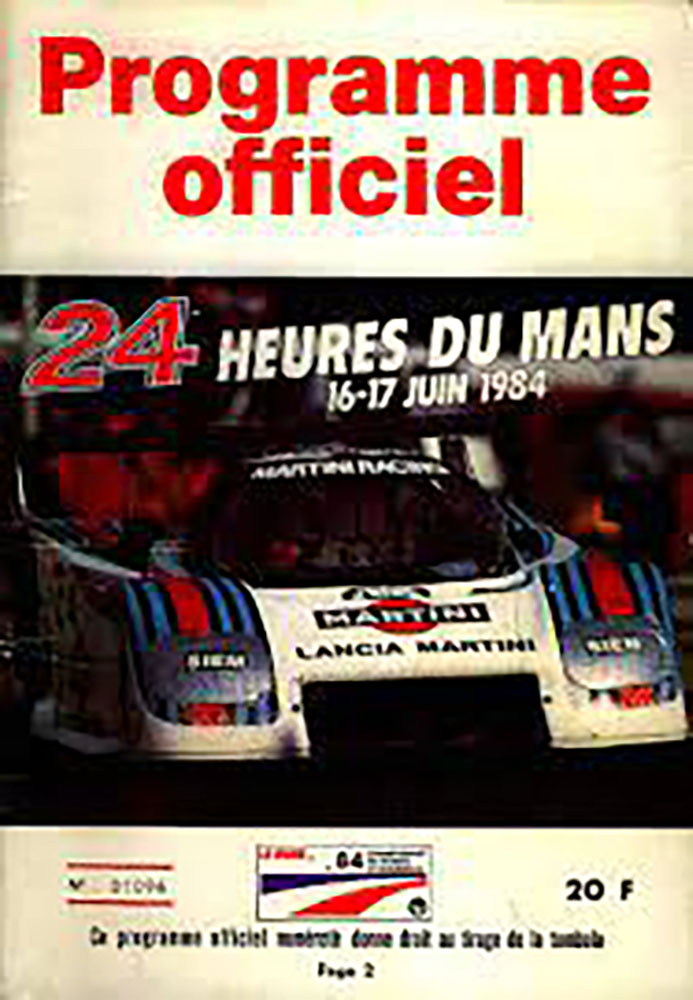

NINETEEN EIGHTY FOUR

IF there was a year that defined the Aussie obsession with conquering Le Mans, it was 1984. Unlike the famous film, this was no dystopia – strong results and a record level of antipodean interest in the French classic the end result of a year that saw the boxing kangaroo feature more than ever before.

The rollcall of Australian drivers to race that year was, frankly, remarkable, with no less than seven racing.

Two were absolutely household names, already both Australian sporting heroes. Another was the defending Le Mans winner while two others were among the greatest exponents of Australian Touring Car Racing – both of them already Bathurst legends and one of them already a two-time winner at the time.

Firstly, there was Alan Jones, the 1980 Formula One world champion with Williams.

Unlike Brabham before him, Jones came to Le Mans following his Formula One peak as he searched for the next phase of his racing life.

He was paired in an all-star combination, too, driving a Kremer Racing Porsche 956B with defending winner Vern Schuppan and French Le Mans expert Jean-Pierre Jarier.

Jones’ Le Mans debut was successful: He, Schuppan and Jarier finishing sixth outright as Porsche swept the top seven places and eight of the top 10 with the crushingly dominant 956.

Also driving a Kremer Porsche was Victorian privateer Rusty French.

Though first and foremost successful in business, though his business Skye Sands, French was a notable Touring Car and GT racer throughout the 70s, 80s and 90s – and still occasionally races today, where he doubles as a co-owner of Supercars team, Tickford Racing.

French’s most notable racing success came in 1983, when he won the Australian GT Championship driving a Porsche 935. He’d finished second to Jones the year prior, too.

It was those Porsche links that brought Grice to Le Mans in ’84 with the crack Kremer team: his drive a reward for his Australian GT success.

Rusty drove with Tiff Needell – well before his days as a notable TV presenter and opposite lock aficionado – and David Sutherland. They completed 321 laps and finished 9th outright.

Further back was Allan Grice, hero to Aussie privateer racers everywhere thanks to his longstanding reputation of taking on the Factory teams at Bathurst and giving them a proper scare.

Like French and Jones, Grice was on debut in 1984, driving another privately entered Porsche 956 with Alain de Cadenet and Chris Craft for Charles Ivey Racing. The car lasted through the night, but was out after 274 laps late in the race.

The man dubbed ‘Oilcan Harry’ by legendary Australian commentator Mike Raymond – playing up his role as the bad guy of the sport – and the future Member of Parliment for Broadwater would return to Le Mans just once more, driving a Nissan Motorsport-backed R88C as part of a limited World Sportscar Championship campaign in 1988.

Having finally won Bathurst in 1986, and as a privateer Commodore driver beaten the Holden Dealer Team at their own game in a European Touring Car Championship campaign, that included the Spa 24 Hour, Grice would finish 14th for Nissan, but wouldn’t return.

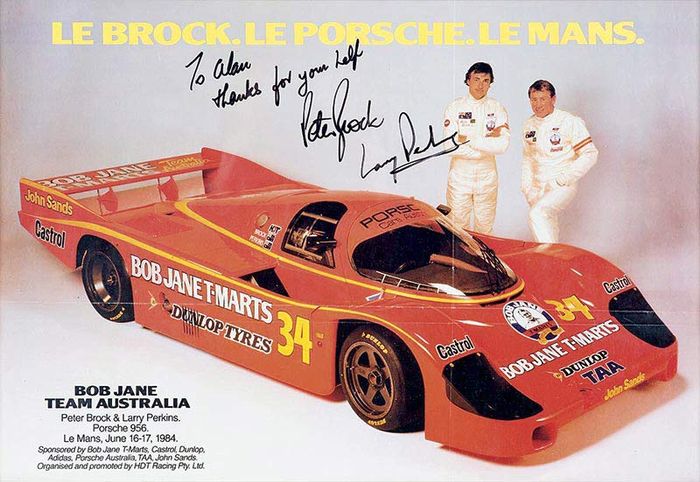

And then there was Peter Brock and Larry Perkins.

With all the heraldry that came from being the most famous name in Australian motorsport, the all-star combination paired the then current-Bathurst champions with another iconic Touring Car hero in Bob Jane, who would fund the enterprise via his massive T-Marts empire.

The Bathurst links continued, John Fitzpatrick Racing secured to prepare and run the Porsche 956 that Brock and Perkins would drive that year. Though he was a Brit, Fitzpatrick’s Bathurst links ran deep – he won the Great Race in 1976, sharing a Holden Torana with Bob Morris in what was an emotional, dramatic victory for the privateers over the factory Dealer Team.

The drivers’ weren’t new to Le Mans, either. Brock had raced there first in 1976, sharing a BMW CSL with fellow Aussie Brian Muir and Jean-Claude Aubriet, lasting 19 Hours before failing to finish.

He was then entered in 1981, sharing a Porsche 924 GT with his Bathurst winning co-pilot Jim Richards and his former Holden Dealer Team teammate, Colin Bond. The car was entered by Porsche Cars Australia, at that point run by local importer Alan Hamilton, himself a former racer. Though high profile and high quality, the team failed to qualify for the race and spent their weekend on the reserve list.

Perkins’ Le Mans debut came between Brock’s first start and the non-event of the ’81 Porsche campaign, driving with Gordon Spice and John Rulon-Miller in a Porsche 911 in the 1978 race. They finished 14th.

1984, however, was to be the big show for both – a chance for two of the greatest Touring Car drivers in Australia, backed by another and in a car fielded by someone who got the Aussie way of going racing. It was, to put it mildly, big news.

All the elements were in place for something big – as the key protagonists explained in this period news piece..

Unfortunately, things didn’t end up quite as they had hoped.

Perkins qualified the car a strong 15th, but despite high fuel consumption and oppressive in-car heat – that forced a driver change at every stop – he and Brock had hauled their bright Orange Porsche into fifth position by the three hour mark.

That’s until a wheel came loose with Brock behind the wheel, just after 6:15pm on Saturday evening. The limp home and repairs cost them 28 minutes, but they remained in the game.

A broken rear rocker arm cost them a further 15 minutes at 9pm, so the decision was taken to press on throughout the night in a bid to make up time.

They had hauled themselves back into the Top 20, when Perkins found lapped traffic in the Esses just before 2am. There was an off, the car ended in the catch fencing just beyond the famous Dunlop bridge, and their race was over.

They had, however, proven a point. Two Touring Car racers and an Aussie sponsor had come from the other side of the world and properly demonstrated their competitive intent. It wouldn’t be the last time.