COMMENT: The Challenges Facing the Future of Motorsport

Previously on The Race Torque, we looked at the massive financial contribution made by motorsport to the national economy as noted in the 2020 Queensland Government inquiry into the industry – here we examine another facet of the report: the many and varied challenges facing the future of the sport.

From adequate facilities to evolving technology, an aging competitor base, government red tape, participant safety, competition from other sports, the retention of competitors and more, there is a multitude of issues that motorsport will face in the short, medium and longer terms.

Do not take this yarn as pessimistic – read it in with an open mind, we’re diving into the challenges outlined in the Inquiry, and simply expand upon them – primarily what we will be racing, and where.

This merely scratches the surface, there are many more valid points and arguments to be had in the coming years and decades from all sides.

Street circuits may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but they serve a purpose. PHOTO: Walker

THE NEED FOR FACILITIES

A constant for all forms of the sport identified in the inquiry was the requirement for access to facilities – ranging from big European-spec professional race tracks to small sealed areas for motorkhanas.

Without venues, there is no motorsport.

Complicating this requirement are trade-offs: for instance, if you build close to major populations you have an easier job drawing an audience, but you almost certainly will upset nearby residents, while rural facilities face less opposition, but will have a harder task in attracting users.

Motorsport venues by nature tend to be large, money intensive beasts to build and maintain, and subsequently, they need a corresponding line up of events and users to make them sustainable.

One suggestion to make race tracks more palatable to the various bureaucracies is to combine the venue grounds with other sports and community causes, as has been done at Morgan Park with various horse facilities included.

Some corners have suggested that money spent on temporary facilities should be pumped into making permanent venues accessible year-round.

The counter to this argument is that the showcase events are a shopfront that brings the sport to the people.

Attracting an audience the size of those seen at Albert Park, the Adelaide Parklands, the Gold Coast, Newcastle and Townsville to rurally based permanent facilities is a very tall order.

Would AFL or cricket be as popular if the commute for spectators was to Phillip Island or Benalla? Albert Park is motorsport’s equivalent to the MCG, and as outlined last week, the temporary facilities tend to stack up from an economic standpoint, ensuring their ongoing funding.

While we typically focus on circuit racing, at the bottom of the motorsport ladder are entry-level disciplines like motorkhanas, which traditionally were able to utilise venues such as shopping centre car parks on Sundays.

However, with the advent of seven-day trading, they have had to move further out away from the population to find suitable homes, with the additional distance a barrier for new competitors.

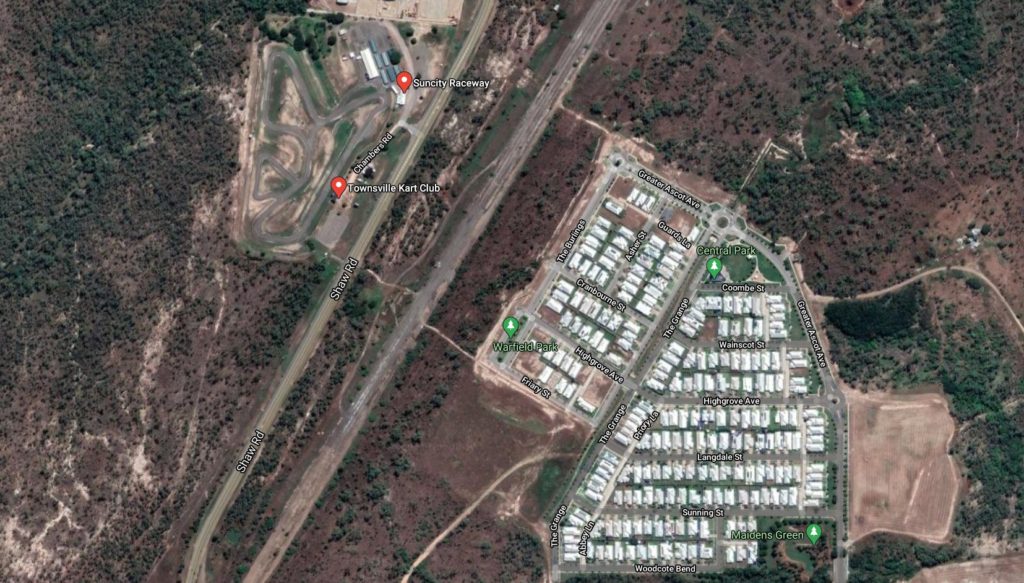

Which came first – Townsville Kart Club or the homes?

CURRENT DAY NIMBYS

The Inquiry noted several instances where motorsport facilities were locked in fights with residents and government bodies.

Perhaps one of the highest-profile cases is Lakeside Park, which we reported on last year, but it is the tip of the iceberg.

Archerfield has long been at war with the Brisbane City Council, with the venue running to tight noise restrictions (such as adopting California’s muffler rules), and limitations on when they can operate, which recently boiled over when the drift track in the venue was effectively shut down.

Further afield, the Townsville Kart Club has spent $80,000 over 18 months to fight local property developers who have moved into the track’s vicinity.

The Carnell Park short circuit at Stanthorpe has come under fire from locals and is only allowed to operate 12 weekends a year.

Motorcycle venues have also been on the receiving end of resident pressure, with facilities at Oxley and Reedy Creek already gone, while others at Labrador, Stanmore and Ipswich are all currently feeling the heat.

The inquiry was told of several possible methods for handling vexatious individuals, including charging repeated complainers an investigation fee, which would be refunded if their complaints were indeed justified.

Meanwhile, in the far north-west, the City of Mount Isa planning regulations do not classify dirt bikes as a ‘sport, recreation or entertainment’, but rather as undefined in its planning scheme.

While planning approval is a constant issue, fees and liability insurance matters have also been a hindrance in establishing new facilities.

Finding the necessary funds to build them in the first instance will also forever be difficult – stick and ball sports merely require a flat patch of grass, motorsport tends to require so much more.

Formula 1 hybrid path is a step en route to the future. PHOTO: Walker

THE TECHNOLOGY CHANGES

Whether you like it or not, the end of the fossil-fueled vehicle is nigh.

Governments the world over are investigating the banning of the traditional internal combustion engine from new car showrooms, highlighted by the United Kingdom’s 2020 decision to expedite the process from 2040 to 2030.

Some of the jurisdictions that have already made similar decisions include California (2035), Canada (2040), China (currently researching a timeline), France (2040), India (2030), Japan (2035), and Spain (2040), amongst others.

Even if some countries don’t commit to change, in the long run, car manufacturers will bring them along for the ride regardless.

Electric technology is ever-improving, batteries are becoming more efficient, and recharging infrastructure is building, while elsewhere, supplemental energy sources such as hydrogen are being developed to power electric motors on longer journeys.

Economies of scale will be reached with regards to vehicle production as well as home (plus grid) battery storage, while the relative cost of producing renewably sourced power continues to come down.

From an enthusiast perspective, electric propulsion has the potential to be incredibly impressive.

While the initial introduction of Formula E was somewhat half baked, with cars that required swapping mid-race, elsewhere, the wares have excelled.

Take for instance the Volkswagen I.D. R, which smoked the Pikes Peak Hillclimb on debut in 2018, becoming the first car to ever break the 8min barrier on the 156 turn, 19.99km course, averaging over 150km/h for the journey.

Then again, 680hp and 649Nm of torque will do that.

Outside of the environmental advantages of not burning fossil fuels, electrically-propelled vehicles, in the long run, will prove to be cheaper to operate for punters on the road, and potentially, with adaptable and upgradable architectures, they will endear themselves to a new generation of enthusiast tuners.

With fewer moving parts, electric engines are typically user friendly in terms of upkeep, even saving on items such as brake pads with thanks to regenerative braking.

This said, will traditionalist rev heads embrace the change, or find a different hobby?

The topic of vehicle operation is also interesting, with autonomously driven machines continuing to be perfected and legislated into public use.

Even now, entry-level microcars are jam-packed with electric gizmos that take the skill of driving into a relatively idiot-proof realm.

Regardless of the types of cars that will be driven in the future, recently, the percentage of teenagers looking to gain their driver’s license has been falling dramatically – if the next generation isn’t interested in steering themselves, how likely are they to engage with motorsport?

The genre has an aging following and overall competitor base – it’s a hurdle that will have to be overcome.

The motoring public as a whole has vastly different vehicle buying habits compared to 20 years ago, with the modern audience seeking practicality above all else.

In 2020, the ten bestselling passenger vehicles featured three utilities (the top of the charts Toyota Hilux and Ford Ranger, joined by the Mitsubishi Triton), four SUVs (Toyota RAV4, Mazda CX-5, Toyota Prado and Hyundai Tucson), as well as three small cars (Toyota Corolla, Hyundai i30 and Kia Cerato).

While looking back to 2000, in the top-ten selling cars there were four big cars (Holden Commodore, Ford Falcon, Toyota Camry and Mitsubishi Magna), four small cars (Hyundai Excel, Corolla, Mitsubishi Lancer and Nissan Pulsar), the light Toyota Echo and a token SUV in the Honda CR-V at number ten.

The first nine of those cars at some stage in the surrounding decade appeared on the grid of an Australian production car race, or in the case of the Excel, spawned into the most popular circuit racing category in a generation.

Another factor that is yet to fully play out in the short term is the cessation of car production locally, as well as the winding-up of Holden, which had the most loyal enthusiast following of all.

This hooked the author on the sport. PHOTO: Walker

THE PAST, LOOKING FORWARD

I’m sure I’m not alone in being attracted to motorsport when I was a kid due to the loud noises and fast-moving bright colours.

I will never forget the whistle of the Ford Sierras and the roar of the Holden V8s.

Many put on their rose coloured glasses recently when Fernando Alonso wheeled out a V10 Renault F1 car, with the engine note somewhat more ear-piercing than the modern hybrid kit.

This hybrid generation of F1 cars has been developed with thanks to the manufacturers involved, who to an extent are seeking relative green credentials that justify their motorsport involvement via perceived social responsibility.

Shifting technology means that the sport we love today will be forced to adapt into the future, however, for all of the possible threats presented, they could, in turn, be a positive spark that will enable the sport to flourish.

For instance, while electric propulsion is currently a strange new world, by the virtue of being silent, the machines of the future could have the ability to quash the NIMBY aspect which is continually a thorn in the side of venues in 2021.

Conversely, if the sport wants to dig in its heels and stick with internal combustion, how will wider society see this?

So, what will the future motorsport landscape look like, and importantly, where will they be racing?

Hit us up on the socials @theracetorque, we’d love to hear your thoughts!