Darlington Park: Murder, Masterplans and a Mountain Pass

In the opening leg of this three-part deep dive into the history of Queensland’s Darlington Park Raceway, we looked at the sequence of events that saw an epic race track built, but never seriously raced on.

Created by Tony Stephens, the race track surface was actually sealed and used by various forms of low-level motorsport over the years, however, at the time of its closing in 2005, much of the supporting infrastructure for a typical circuit had not been put in place.

Since its inception, there was much talk in the media about the possibilities of the facility, which at one time claimed that both the World Motorcycle Championship and Formula 1 was on the agenda!

Here we delve into the finer details of the venue, the circuit, the masterplan, its users, plus much more…

Looking back up the hill from the middle of the main straight. Photo: Mark Walker

A Hot Lap

In its final guise, the Darlington Park layout was an absolute belter.

The author visited the facility in February 2001, and was told at the time that the intention was for the big, long straight would be home to the start/finish line and pits, as above.

Quite how this would have worked with a decent paddock area would have been interesting, as the hillside tailed off significantly on driver’s left towards a creek.

At around 730m long, the straight descended to a sweeping, slightly off-camber right turn one, not entirely dissimilar to the opening corner at the old Surfers Paradise International.

A relatively open right-hand hairpin followed, relatable in radius to Lakeside’s Karussell or Eastern Loop, followed by a fast left-right-left series of sweeps (below), which for the most part continually gained elevation, with a chicane thrown into the mix for motorcycles.

This section then opened up to float over a pair of crests, firstly through an on-edge left curve, followed by a flat out right-hander, prior to some hard braking at the subsequent right hairpin.

Images from the period depicted the grid starts for motorcycles in this area, with crowds perched on the massive hillside to driver’s left.

The following ‘straight’ featured a flat left-hand bend, like the old back straight at Morgan Park, with another right hairpin shortly afterwards.

Two short straights were split by another acute left, with the final tight right leading quickly into a flat left kink at the top of the straight.

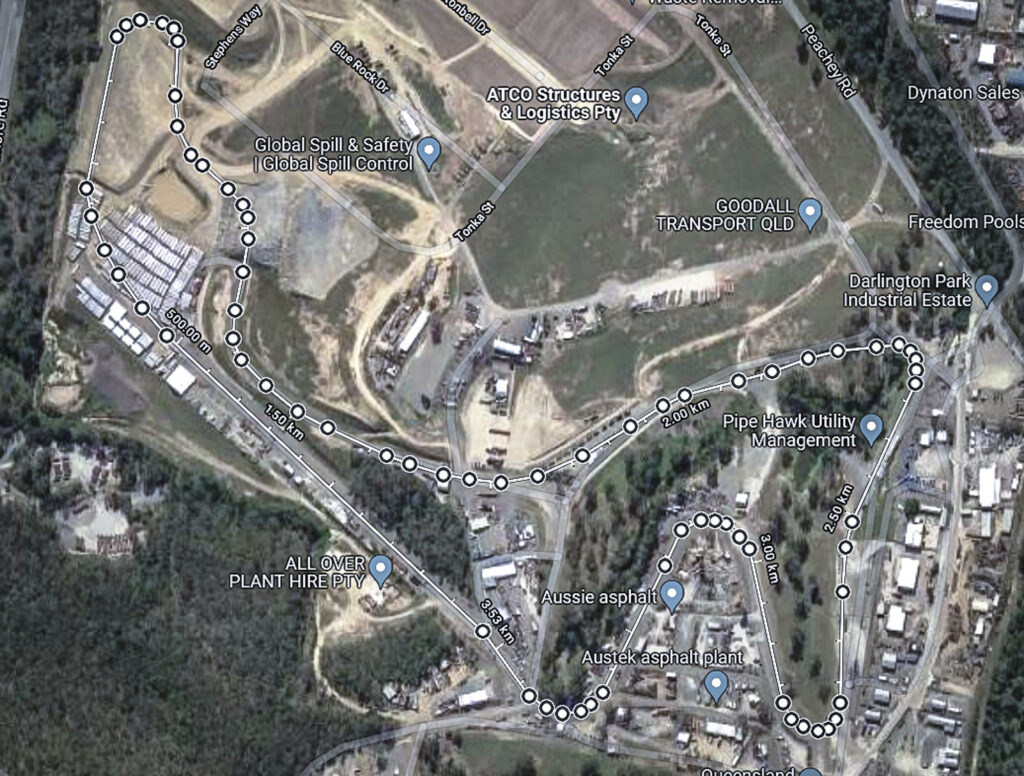

Modern-day measurements taken from Google Maps calculate the final full track at 3.53km, and complete with around nine different link roads, there were many different configurations available to users.

Added into the mix, several large skid pan areas were sealed, ditto a significant hillclimb/go-kart track, which was located towards the northern end of the complex.

While all of the above track surface was actually in place, precious little other of the typical infrastructure to complete a classic race track was visible, although the facility had acquired different pieces from the former Expo 88 site, which formed the basis of an entertainment area at the top of the hill.

Solid walls were few and far between in the beginning, with one of the few permanent examples that saw reality positioned at right angles to the circuit immediately at the end of a hard braking area (see: image at top of story).

Gravel traps were minimal, with much of the circuit naturally tree-lined.

While the layout was a thrill to drive, it suffered some fundamental flaws – it didn’t leave much scope for run-off zones, such as at the first turn, which ran hard up against the property line of the site, or turn five, which brushed up against the main straight.

But that depends on which way you ran the track…

Which Way Around?

While the above description of the circuit is true for practically all of its users, it was actually contrary to Tony Stephen’s vision for the circuit.

Much like Lakeside Raceway, the circuit’s flow flipped after opening.

“He always designed it to run the other way to what everyone else was running,” said Gene Corbett from Total Driver, whose company operated at the venue.

“Everybody ran the track clockwise, simply because it was easier to manage people doing down into the kink (turn one) than if you were going the opposite way, coming up over the crest, getting them to brake and turn, there was no real run-off, it was just a bit of a recipe for disaster.”

If the clockwise direction of travel that everyone experienced was wild, the reverse lap would have been one non-stop pucker moment…

Top left: the final layout used, as per Google Maps.

Top right: the planned circuit including the tour via Mount Darlington.

Above: A look at the potential mountain pass section, from Google Earth.

The Masterplan

A billboard erected at the entry to the facility in 1998 made some interesting reading.

The opening stage, which was completed to that point, and essentially consisting of the circuit’s final form, came to a cost of $74.5million.

The second stage was to include music bowls and stages, boardwalk shops, a ‘Darlington Members Club’, vineyards, a vintage car museum and theme rides, which would elevate the project value to $106million by the start of 2003.

An extensive planting of grapevines actually filled the outfield near the top of the main straight, which was planned to be combined with the typical winery trimmings and a massive music bowl (located adjacent to the go kart track), a package along very similar lines to what eventuated just up the road at Sirromet.

The third and final stage included the extension of the main racing circuit through to Mount Darlington (180m above sea level), plus a chair lift and horse riding ranch, with the final forecast price coming in at $240million.

The extension to the top of the mountain, above, would have provided a layout that had the potential to throw shade on Mount Panorama.

The road was indeed carved through the area to the top of the hill, around the perimeter of the facility’s quarry – it would have provided an undulating free-flowing blast, with the outline still visible on aerial images to this day.

This extension up Mount Darlington would have been around 2.39km long, and when bypassing the infield loop section and its grapevines, it would have resulted in a 5.24km long circuit with corners adding up to the mid-20s in number.

Also mentioned in different articles over time, there was a desire to include a quarter-mile drag track and speedway dirt oval, a 4WD track, trail bike tracks, a BMX track, a mini bike track and a driver training centre.

What could have been…

Beyond the Mitsubishi Magna is Mount Darlington, the rise which could have played host to the third and final stage of the master plan. Are you getting Mount Panorama vibes from that? Photo: Mark Walker

Murder in Yatala

People started talking when Tony Stevens was murdered at the former Bullens’ Lion Park in Yatala on September 11 1997, 2km from Darlington Park.

The race track was a significant issue in the local area, with the murder even making it into the pages of the specialist national motorsport press.

However, there was an important distinction to make: Tony Stephens, the owner of Darlington Park, was definitely not the same person as accused drug dealer Tony Robert Stevens, who was shot in the back of the head by Darren Michael Golledge.

Golledge and Stevens (who lived in a vacant house in the Park) were involved in a violent attack on the Park’s caretaker Michael Weir, before Golledge turned on Stevens.

All a little too close to home in more ways than one.

The V8 Experience at Darlington Park – a concept ahead of its time. Photo: Mark Walker

Up and Running

Numerous businesses wound up operating out of Darlington Park.

The Top Rider motorcycle business was a mainstay, with the organisation running their own lowkey race events, alongside practice days and an extensive training and tuition offering.

In the latter days of the venue, Total Driver utilised the facility extensively for a wide range of four-wheel programs.

Over the journey, Darlington Park was a favourite with car companies such as Nissan, Toyota, BMW, Range Rover, Porsche, Mercedes, Volvo Trucks and more for launches and drive events, whether the track was sealed or not.

The Glenn Stewart owned V8 Experience (above) used a shortened version of the circuit for its operations, with customers able to jump behind the wheel of the modified AU XR8 Falcons for ten-lap stints.

Ultimately, the business would morph through separate ownership into today’s nationwide enterprise.

Elsewhere in the complex, the hillclimb/go-kart track was home to a popular hire kart business, MSI Karting, which was later rebadged as Karting in Paradise, below.

Featuring some serious elevation changes, the 1.3km layout was in the end altered with the addition of a chicane to the outfield to slow speeds on the long downhill main straight.

The track played host to many famous faces from the local motorsport scene, with a charity race at the venue won by Frenchman Nelson Philippe.

For Philippe, the Gold Coast area was a charm: he claimed his lone Champ Car victory on the streets of Surfers Paradise in 2006, while he also claimed Miss Indy winner Sarah Buller, with the pair hooking up after that year’s beach volleyball match.

Outside of motorcycle racing, the main track was used for club sprint days for four-wheeled machines, rally sprints, motorkhanas, legs of the Dutton Rally and more.

In 2001, the Gillette Young Guns used the facility to test out their Honda Integra Type R’s ahead of their shootout on the streets of Surfers Paradise, with drivers including Will Power, Jamie Whincup, Dean Canto, Adam Macrow, Owen Kelly, Luke Youlden, Mark Winterbottom, Troy Hunt, Peter Hackett and James Manderson.

The lack of motorsport infrastructure in place also made it a favourite for filming, with multiple productions over the years utilising the venue.

Those who drove the circuit came away with plenty of battle stories, from machines firing off into trees, walls, spoon drains and lakes, it wasn’t a track for the faint of heart.

Folktales of notable pilots landing on their heads also pockmark the memories of survivors.

The go-kart track that blasted its way through the valley. Images: Mark Walker/Google Earth

The Norwell Motorplex today, showing what is capable on a smaller scale. Photo: Mark Walker

Elsewhere in the Local Area…

After initially lending a hand with design guidance at Darlington Park, by 1990, the Longhurst Family and Frank Gardner had opened The Benson & Hedges Performance Driving Centre some eight kilometres to the east of Darlington Park, above.

With the backing of BMW, the $3million venue featured a 2km long test track, complete with a skid pan and turntable.

At the time of its launch, in conjunction with Australian Airlines and the Hyatt Group, the Centre offered two and a half-day courses aboard 3 Series BMWs at a cost of $500 a pop.

The facility has morphed into the modern-day Norwell Motorplex, as operated by the Morris family.

Many other local proposals for facilities however would come and go without being a sod of earth turned.

Before Darlington Park came onto the scene, the former owners of Surfers Paradise International Raceway, the Westmark Corporation, proposed building an international standard circuit on the former site of Bullens’ Lion Park (the location of Tony Stevens’ murder), which closed its safari gates in 1988.

Word is that trial low-level motorsport event actually took place at the site, including a rallysprint.

Located adjacent to the current M1, just north of the Carlton and United Breweries and the ex-Tekno Autosports base, the venture fell onto the back burner, and attention instead shifted to upgrades at Lakeside Raceway, which ultimately saw earthwork carried out on potential NASCAR and dirt speedway ovals on the inside of Hungry Corner.

These works, along with other planned extensions to Lakeside were never completed, with efforts grinding to a halt in May 1989.

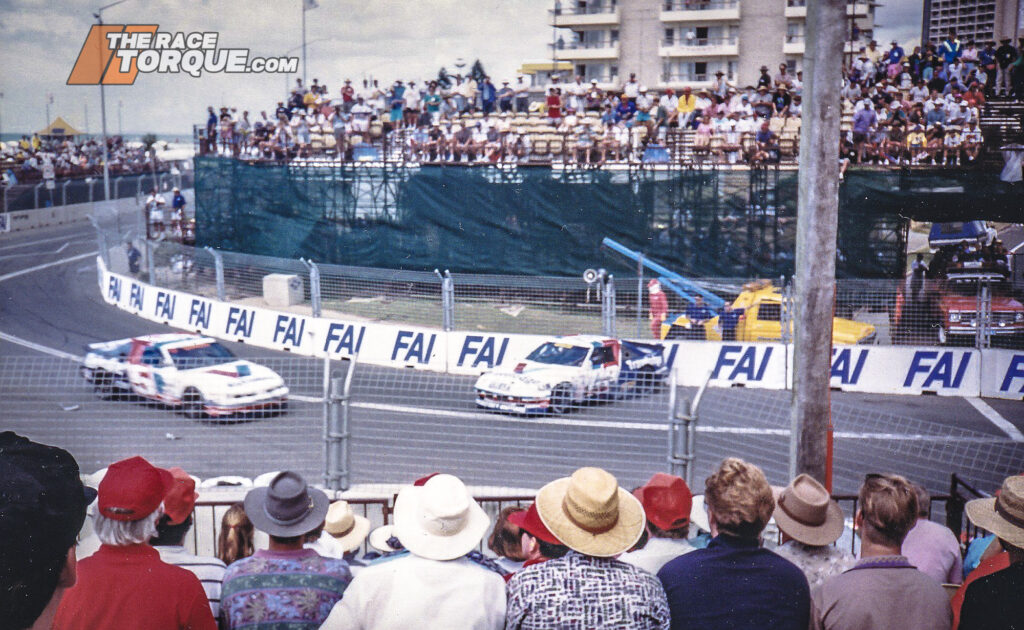

While the Indycar street circuit came to fruition in downtown Main Beach in 1991, above, it was surrounded by other ambitious projects, including a facility adjacent to the Gold Coast Seaway named Pacific Park in 1990

The permanent track was to be located at the northern end of the Spit, an area which is now used to store team transporters during the Gold Coast 600 weekend, and the subject locale of ongoing (at times heated) discussion around potential uses, including a cruise line terminal.

In 1996, there was also a proposal for a significant venue to be built adjacent to Dreamworld, with a 3.3km circuit costing $15million.

At the same time, Ross Palmer was investigating a pair of Gold Coast hinterland sites.

The Cockatoo Creek project would later adorn the sides of Ian Palmer’s radical Nations Cup Honda NSX, with the country club styled facility never becoming a reality.

More recently, the ambitious i-METT project came to light in April 2007, with the world-class venue set to take over the cane fields of the northern Gold Coast, on the eastern side of the M1 from Darlington Park.

With a price tag between $650million and $2.5billion, the project fizzled out in around 2015.

The one local venture that actually saw the light of day was Queensland Raceway, some 55km to the west, with that site’s opening in 1999 slightly behind the soft launch at Darlington Park.

Noisy Business

Noise is the enemy of motorsport venues everywhere, with the Gold Coast area synonymous with venues coming under fire.

A point in case is the Gold Coast Motocross Club, whose Stanmore Park facility is located within one kilometre as the crow flies from Darlington Park – both venues are located on Stanmore Road.

Originally built by the Albert District Motorcycle Club, the use of the site dates back to at least the early 1980s, prior to any movement at Darlington Park.

Stanmore Park survived a tumultuous period through the early part of last decade, when it and the similar facility at Reedy Creek were shut to be replaced with a greenfield site at Stapylton.

The project in the end was bungled by the Gold Coast City Council, with $1.16million wasted on the venture in 2011. The mismanagement was later subject to an independent audit.

Reopened, Stanmore Park has been the subject of ongoing issues, although it recently sealed a lease extension that is renewable through to 2026.

Elsewhere on the Gold Coast, the Mike Hatcher Motorcycle Club in Ashmore has suffered continued pressure, while the Xtreme Karting facility at Pimpama hit the headlines last year when it was shut following issues with the venue’s planning approval, with a fresh development application currently being crafted for Council consideration.

The former home of the Gold Coast Kart Club, Days Park Raceway in Coomera, was shuttered in 2008, with the status of a replacement venue at Woongoolba still in limbo.

For more on Darlington Park’s noise issues, stay tuned for our final instalment…

The Dream is Over

Following the closure of the raceway, the Stephens family have developed the 127ha site into the ten-stage Empire Industrial Estate, hosting 550,000sqm of buildings zoned for a variety of uses, from light to heavy impact industry, providing jobs for up to 5,000 people.

Major tenants to date include Caterpillar, COPE Sensitive Freight, ATCO and Stihl, amongst others, with many of the project’s blocks spoken for.

The area is still the home to the Crushing Dynamics Yatala Quarry, which specialises in hard rock products such as aggregates, road base, fill material and dust.

Elsewhere locally, Hanson and Holcim have similar major quarries of their own.

While some of the roads on the new development follow portions of the old track, practically all evidence of the circuit is gone.

For any local residents who complained about the raceway, they are now left with a legacy of heavy industry and non-stop large trucks.

While Tony Stephen’s “build it and they will come” field of dreams race track never became a reality.

Next up on The Race Torque, the Darlington Park story concludes with the tale of a secret car company project that could have drastically altered the future of V8 Supercars competition…

Click here to read the final feature in this three-part special.