Before the Great Race: Bathurst’s First Enduro

After three formative years beating around the Phillip Island Circuit, Australia’s Great Race transferred to Bathurst in 1963 – however, that wasn’t the first time an enduro was contested on the undulations of Mount Panorama.

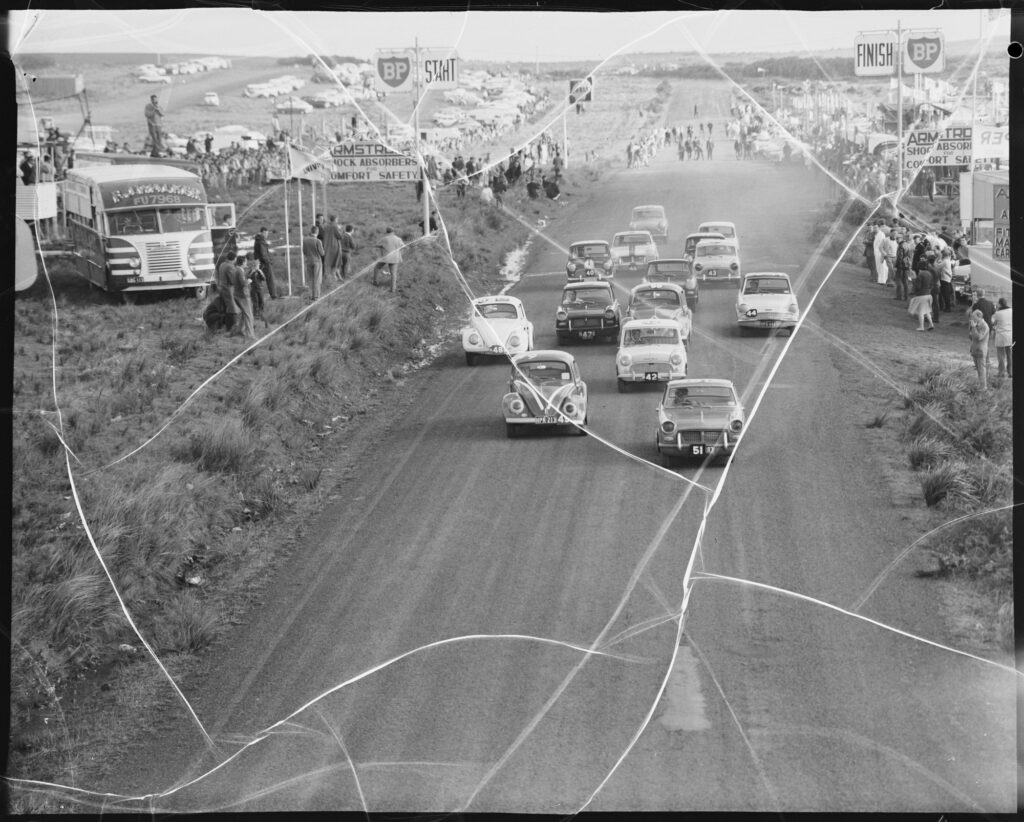

The 1962 Armstrong 500, plus that blasted bridge… Images: State Library of NSW and the Victorian Collections

Island Origins

In the beginning, the event we now love as the Bathurst 1000 was founded with a trio of 500-mile races for production touring cars at Phillip Island from 1960 to ’62.

With backing from Armstrong shock absorbers, the original idea was to hold a long-distance race on the former Albert Park Grand Prix Circuit, however, when that option fell through, the Island became the obvious choice.

Name drivers and widespread interest drew bumper fields to the contests – in essence, the feature events for tin tops at this time rather than the previously preferred open wheelers changed the course of motorsport locally forever.

Manufacturers of the day could see the tangible benefits of testing their machines out in the heat of competition.

The biggest issue facing Phillip Island’s circuit was access – the shaky old suspension bridge wouldn’t take the load of heavy-duty road-building equipment, so the racetrack was topped by a “cold mix” process, which as it transpires was far from capable of coping with the rigours of large fields of cumbersome sedans.

The events proved to be the biggest in the history of the venue, but potholes and a flaking surface were key storylines in each race.

Initially organised by the Light Car Club of Australia, the circuit’s custodians, the Phillip Island Auto Racing Club upped the weekend lease fivefold in 1961 to £2,500 to help cover track repairs, before the LCC handed over the reins of the event to PIARC for its final Victorian running, as it focussed its efforts on the new Sandown Park venue rather than cough up for the ever-inflating rent.

For that October 21st 1962 event, four classes were set along price lines, with one of the key rules being the requirement to have laminated windscreens fitted, which in hindsight, was a blessing.

Rain leading into the meet deteriorated the track surface, which started to fall apart during the preliminaries.

A massive pothole developed during the race at Siberia, while marshals moved their posts away from the track edge to dodge the shrapnel spray from the crumbling circuit.

Outside of the racetrack surface, a fiasco developed in the timing and scoring of key competitors, while further post-scrutineering disqualifications left a sour taste in the mouths of many.

Armstrong sought to move its event – it is noted in the record books that options included Lowood and Lakeside in Queensland, Longford in Tasmania, Sandown and Calder in Victoria, plus Warwick Farm in New South Wales.

Ultimately the race landed at Bathurst, with the meet to be organised by the Australian Racing Drivers Club.

However, before that inaugural Great Race on the Mountain in 1963, there was another enduro on that famed 6.172km long scenic drive, and it happened just before the final Armstrong 500 on the Island…

The 1962 Bathurst Six Hour Classic

The ARDC had taken over the organisational rights for four-wheel motorsport at Mount Panorama in 1954, with the competitor-centric club drawing in audiences through high-quality fields.

Whether the 1962 Bathurst Six Hour Classic was an audition to take over the Armstrong 500, or simply a play to trade on the success of the concept, the event contested on the 30th of September was a hit.

Unlike the Phillip Island meet, and future Bathurst enduros of the era, the Six Hour was open to not only showroom stock production cars, but also production sports cars.

Interestingly, there was no official classification or recognition of the official winners, with the race split into six groups, namely production touring up to £900, £901 to £1,050, £1,051 to £1,250, £1,251 to £1,700, with the production sports split between up to £1,500 and up to £2,000.

In today’s money, the top value of the eligible volume produced Australian-made or assembly machinery was $61,000.

If anything, the ethos closely followed the early 1990s regulations for the first iteration of the Bathurst 12 Hour, which featured run-of-the-mill road cars going up against Porsches and the like.

A total of £3,000 prize money was up for grabs, split evenly between the classes, with each winner receiving £300, second £120 and third £80, with contingency sponsors tipping in an additional £2,000.

Each entry required two drivers, who needed the relevant CAMS license, although the acronym stood for the Commonwealth Amateur Motor Society, with the other main condition of the race being strict post-race scrutineering of the top six in each class, with engines and transmissions to be torn down.

Pre-event publicity focused on star entries, including the Daimler SP250, Triumph TR4, Morgan Plus 4, and Austin Healey Sprite, with the quicker sedans including the Fiat 2300, Fiat 1500, Cooper Mini and Datsun, with the two new Austin Freeways a feature of the 51 cars covering 28 different models entered.

There were some absolute oddities thrown into the mix as well, such as the Cummins/Johnson Hillman Husky Van, below, which was a testbed for the Sunbeam Tiger, as fitted with a Ford 260 cubic inch V8!

Top teams entered included the Geoghegan Brothers and their Daimler, Arnold Glass/Noel Hall for Datsun, Carl Kennedy/Doug Stewart in a Simca, Bob Jane/Harry Firth in a Ford Falcon, Burns/Crampton in a Fiat 1500, Dave McKay/Greg Cusack also in a Fiat 1500, Bill Buckle/Brian Foley in a Citroen, and Frank Matich in a Morgan.

Other drivers who failed to make the publicity cut for the event included John French, Peter Wherrett, Barry Gurdon, Bob Holden and Fred Gibson.

To say there were some unique Bathurst podium finishers from the event is somewhat of an understatement.

The baby car Class A was dominated by the Morris 850, with the win claimed by the Frank Kleinig/ Frank Kleinig Jr father/son combo, with the West/Pitt Skoda Super Octavia sneaking onto the podium.

Skoda claimed Division B with a Felicia model as driven by Martin/Hodges, ahead of a pair of Morris Major Elites, while Morris struck back in Division C, with the Cooper as driven by Bruce McPhee and Barry Mulholland victorious ahead of the pair of Austin Freeways.

Ultimately, McPhee and Mulholland would prove successful in the 1968 Hardie-Ferodo 500 aboard an HK Monaro GTS327.

The outright tourers were won by Don Algie/Kingsley Hibbard in a Studebaker Lark ahead of the Fiat 1500s of McKay/Cusack, and Peter Williamson/K. Whightley.

In the cheaper sports cars, Tony Reynolds/Les Howard claimed a win in their Morgan Plus 4 ahead of the Kevin Bartlett/Bill Reynolds Austin Healey Sprite Mk1, and the Owen/Wear MGA 1500, while in the top tier, Leo and Pete Geoghegan were clear winners by four laps in their Daimler SP250 from a pair of Triumph TR4s, completing a total of 104 circuits.

For comparison with the modern version of the Six Hour, in the safety car marred 2018 race, the winning Sherrin BMW completed 109 laps, while in 2019, Beric Lynton and Tim Leahey set a new benchmark with 131 laps, which also included the additional circuit length covered in The Chase.

The one major casualty of the race was the Jane/Firth XK Falcon.

After Firth drove the car to Bathurst from Melbourne, the duo were the fastest sedan in the preliminaries, however, the brakes on the big car were suspect at the end of the straights.

A little after the two-hour mark, Firth locked up into Hell Corner and rolled, flattening the Ford – these were the days before roll cages, such was the emphasis on being stock standard.

The Fox alighted from the mess largely uninjured via the back window.

Back at the Ford Motor Company base, the team were already working on a new XL model Falcon, which wound up leading home the Armstrong at Phillip Island a few weeks later.

Meanwhile, it wasn’t all plain sailing for the Geoghegan brothers, above, who stripped first gear at the start, and were forced to juggle between two remaining cogs for the remainder of the race.

The Daimler SP250 was a rare beast, with only 2,654 produced over a five-year run from the then-Jaguar-owned factory.

With a 2.5 litre V8 powerplant, a lightweight fibreglass body and disc brakes, it proved to be a potent combination – even if the driver’s door swayed open as it made its way around the course!

By the time of the next enduro, the sports cars were gone, and the timed finish was replaced with a 500-mile length.

From 1963, the Armstrong 500 found its new home on the Mountain, and the motorsport world a new crown jewel event.