The Great Bathurst Tragedy of 1955

1955 was an awful year for motorsport.

Infamously, on the 11th of June, the world was rocked by the tragedy at Le Mans.

When Lance Macklin’s Austin Healey swerved to avoid the slowing car of Mike Hawthorn, the Brit came into contact with Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR, which hurtled into the crowd, killing Levegh and 84 spectators, injuring scores more.

Consequentially, many countries banned motorsport, some temporarily, others long term, including Switzerland, which remained steadfast in its sanctions through to 2022.

The unpacking of that event has been the subject of books, movies and much analysis, with the learnings from the incident in due course leading to improved safety standards around the globe.

Exactly two months prior to that fateful day in France, Mount Panorama, Bathurst, suffered the worst accident in its then 17 years of existence when an eerily similar mishap occurred, with a car entering a spectator area, killing two and injuring 17 others.

A Black Easter Monday

Racing in Bathurst at Easter is a staple – the tradition dates back to 1938 when Mount Panorama first opened, and even earlier on formative circuits across the district.

Placing 1955 on a timeline, it was an era of significant change for the circuit.

The previous year saw the Australian Racing Drivers Club take over the organisation of car racing at the venue, after the relationship between the previous custodians, the Australian Sporting Car Club and the local bodies dissolved.

That same year, a new control tower was constructed by the Bathurst City Council, while power lines throughout the facility were made permanent.

Come Easter 1955, Reid Park had been created on the northern slope of Mount Panorama, an area that was joined to the bottom of the hill by the opening of Barry Gurdon Drive, which descended past the Bathurst Rifle Club to join up with the extension of pit straight.

The ARDC also acquired a large parcel of land inside turn one, which extended up to the Mountain Straight gates, while state-of-the-art timing equipment was utilised.

Additionally, Conrod Straight was widened to 8.5m wide, with a fresh tar seal applied.

Interestingly, spectators in those early days had much freer access to explore the areas surrounding the circuit, with punters lining the outside of Conrod Straight all the way up to Forrest’s Elbow.

In front of a record crowd estimated in the region of 35-40,000, the headline race of the meet was the Bathurst 100, scheduled for 26 laps at 2:15pm on Easter Monday, featuring the Grand Prix stars of the day.

Reg Hunt’s Maserati was the fastest car down Conrod for the weekend, clocked at over 230km/h, Stan Jones was there in his Maybach, Alec Mildren had a Cooper Bristol, and Lex Davison was aboard his HWM Jaguar.

Starting mid-pack with a 9min32sec handicap was Gordon Greig from Newcastle aboard the Alfa Alvis.

On lap 16, Greig pitted after feeling ill, with 30-year-old Sydneysider Tony Bourke taking the controls, after he had been waiting in the pits as a crew member for the car.

Over the final hump in Conrod Straight, just short of a full lap out from the pits, the machine reportedly suffered a flat tyre, fishtailed, spinning and almost rolling, before veering sideways through the trackside wire fence.

Burke alighted from the car under his own power in the spectator area, with the Alfa Alvis facing nearly 180 degrees to the direction of traffic. He was later treated for shock.

The car somehow missed a rather solid gum tree.

Ambulances, support vehicles and a throng of people converged on the scene, despite the pleas of announcers over the PA, the police and the ARDC officials for calm.

One newspaper report noted that officials later criticized “the crowd’s morbid curiosity”, while one of Burke’s crew told a reporter that the team were preparing a sign to ask him to pit.

The race continued, albeit at a slowed pace past the accident scene.

As this chaos was unfolding, Les Murphy lost it just up the road at Forrest’s Elbow, with his MG Q hitting the earth wall and ejecting the driver, who had his foot stuck between the pedals.

Narrowly missed by other competitors, he dragged himself off the circuit with a broken leg.

The wreckage from these two incidents can be seen in the video above.

The emergency response called for all hands-on deck – Bathurst’s four ambulances were pressed into service, ferrying the injured to the Bathurst District Hospital under Police motorcycle escort, with doctors called in to assist at the makeshift triage centre.

Others were treated at the scene for minor lacerations and shock.

Sadly, Gavin Larnach, a seven-year-old from Lambert Street in Bathurst, passed away en route to the hospital, while five people were admitted in a serious condition.

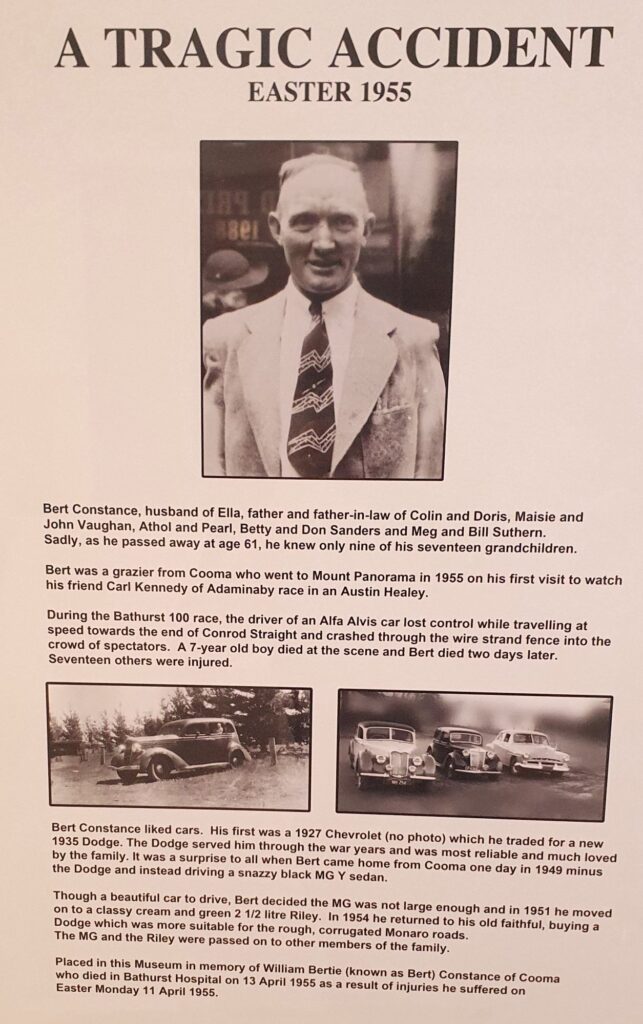

On the 13th of April, Bert Constance from Cooma succumbed to his injuries following surgery – a memorial celebrating his life and love of all things automotive remains today in the National Motor Racing Museum, above.

A newspaper story on the 27th of April noted that ten injured people remained in hospital at that time.

The Aftermath

It was the second fatal accident over that second hump in Conrod, and sadly, it wasn’t the last.

Inquiries were made, although the matters were essentially kept quiet, with portions of the court proceedings most uncomfortable for the victims and their families.

In classic motorsport style, reactionary changes were made at Bathurst – for the October 1955 meet, spectators were banned from Conrod with the exception of the final section, which was protected by more sturdy fencing.

Later, fans would be removed from the area altogether.

Moves were made ahead of the 1982 Great Race to open spectating back up on Conrod Straight, with the installation of the JPS bridge over Conrod, although that was never properly utilised until 1988 when after the addition of The Chase, spectators were once again able to see the cars reach terminal velocity.

Period photos from 1955 show the heaving spectator areas without any genuine first line of protection – in hindsight, it was a recipe for disaster.

These days at the location of the crash, spectators are protected by a concrete retaining wall and international-spec sturdy catch fencing.

Greig ultimately put the Alfa Alvis up for sale, while Bourke passed away in July 1965 following a Midget crash at Westmead Speedway.

Immediately following the events of Easter 1955, the media whipped into a frenzy.

An editorial in The Canberra Times entitled “Death as an Amusement” started with:

What has been described as the worst accident on the Mount Panorama racing circuit near Bathurst, gives a revealing glimpse of one of the gravest problems that has to be surmounted in the promotion of road safety, namely the low value that is set on human life. Apparently, spectators invaded a danger zone, ignoring the precautions that had been provided, and no one cared very much about stopping them. This speed racing, however, attracts large crowds, to whom one of the thrills is that cars overturn and drivers run the risk of injury or death in a thrilling entertainment. The racing of cars on these tracks is not a reliable test of the machines, the reliability of which may be demonstrated more sanely, but it is a test for the dare devil spirit which is capable of being encouraged more usefully in a variety of other ways. In this respect, they resemble the gladiatorial contests of ancient Rome, except that in those days, the lions were not permitted to get among the spectators, and the spectators were not permitted to invade the arena.

The Mayor of Bathurst, Alderman A.L. Morse, responded by noting that the spectators involved in the accident had every right to be standing where they were.

Macquarie Street meanwhile swung into action, implementing the New South Wales Speedway Racing (Public Safety) Act of 1957, in response to the events in Bathurst, other earlier speedway incidents where members of the public had been involved, and no doubt the Le Mans disaster.

You can read the initial Act here.

This clamp-down ensured that the carefree laissez-faire early days of the sport were gone.

Multiple venues didn’t survive the implementation of the Speedway Act, such as Gnoo Blas, Mount Druitt and more, in a move that throttled the sport’s growth for a generation but was correspondingly responsible for raising safety levels.

The Act has morphed over time into the Motor Vehicle Sports (Public Safety) Act 1985.

Easter 1955 is one of the saddest chapters in the legend of Mount Panorama, a reminder that motorsport is dangerous, but from the worst of happenings, lessons can be learned, and improvements made.