Wrong Year, Wrong Name: The 1937 AGP

It was held in the wrong year and wasn’t even referred to as the Australian Grand Prix, but what we now know as the 1937 AGP from South Australia’s seaside Victor Harbor has grown in stature to become a landmark event in our motorsport history.

Historic images with thanks to the State Library of South Australia

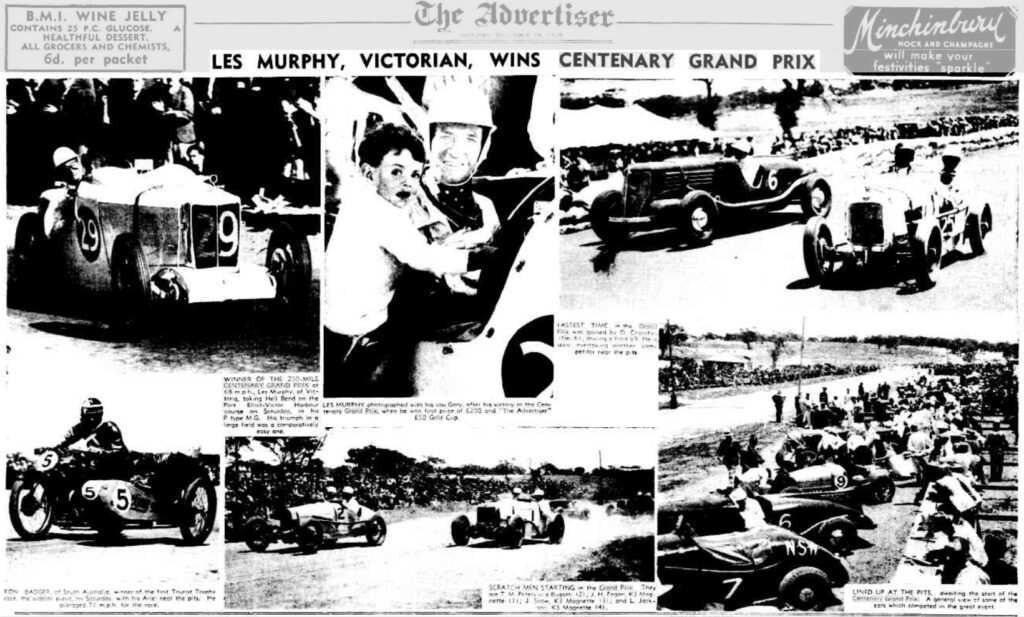

In an asterisk for the history books, this 1937 event was actually held on Boxing Day in 1936, with it being known at the time as the South Australian Centenary Grand Prix, one of the many state government-backed initiatives as a part of festivities during that year.

Over time, the meet rebranded itself to find its place officially in the history books, although that wasn’t entirely unprecedented, with the inaugural AGP at Phillip Island known at the time of its running as the “100 Miles Road Race”.

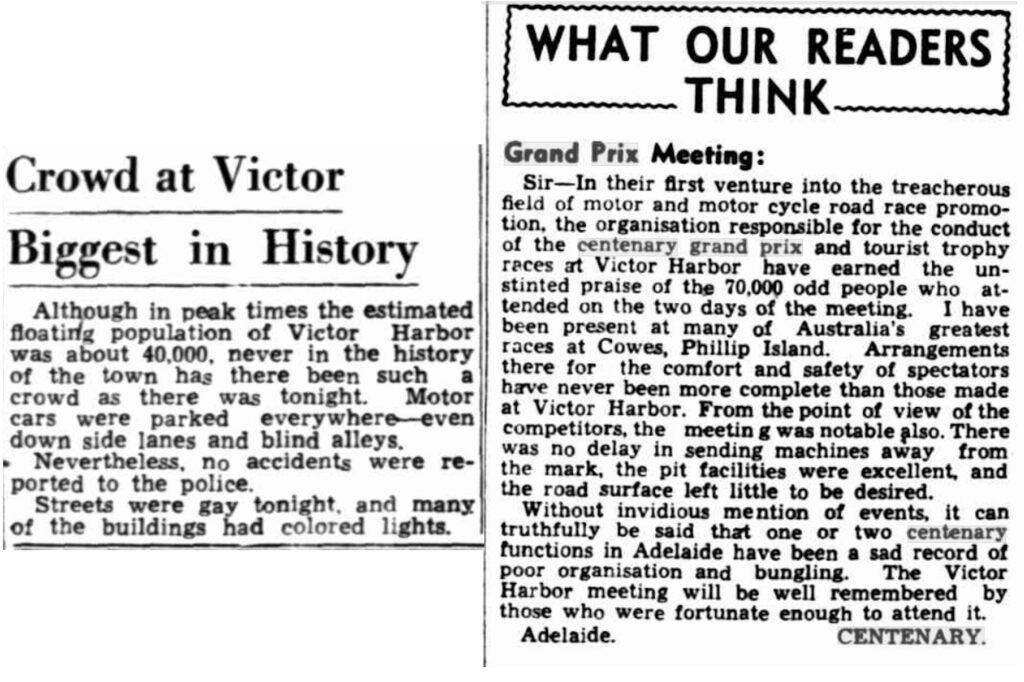

In true SA style, like the Mad March of modern times, it was thought that the packed calendar of events around December would detract from each other, but the opposite was seemingly true at the GP.

Another celebratory fixture was the ‘South Australian Centenary Trial’ or ‘National Motor Car Rally’, which started in Melbourne, Sydney, Perth and Broken Hill before finishing in Adelaide on December 22, with the press noting that post-rally, competitors had time to make their way south to watch the Grand Prix.

That particular event was recognised as being the nation’s first true great motoring challenge prior to the Redex Trials officially kicking off in 1953.

Of note, the Victor Harbor meet was the first Australian Grand Prix not to be contested on Phillip Island, the venue of the opening eight events stretching from 1928 to 1935, making it the opening race in a long line of meets that toured the country state-by-state.

The AGP sequence has only subsequently been disrupted by War and pandemic.

Furthermore, it was the first official four-wheel race contested on public roads in South Australia, forcing the amendment of the Road Traffic Act, with the tradition of road racing continuing to this day on the downtown streets of Adelaide.

In other things, the race is widely recognised as being held in Victor Harbor, although much of the track was located in Port Elliot, which is situated down the road and around the corner from the modern-day South Oz holiday hot spot.

The Sporting Car Club of South Australia, founded two years before the meet, was noted as providing much of the organizational grunt work around the race.

However, the SCCSA wasn’t new to the Fleurieu Peninsula, having earlier hosted events contested further south near The Bluff, with activities including a quarter-mile acceleration test, a half-mile stop and restart test, and a half-mile hillclimb.

The Meet

A big occasion deserved an appropriate program, with the event stretching over four days to conclude with motorcycle races on December 29th.

Like the contemporary Adelaide 500, the Centenary Grand Prix featured a stacked schedule that included a full undercard of supports, with the main race said to have attracted over 40,000 to 50,000 spectators, with 1,000 to 1,200 housed in a grandstand.

In the lead-up to race day, it was noted that competitors unofficially tested and tuned their machines on the course from 5am on December 19th.

Temporary accommodation was sought, with multiple publications noting:

Special Camp for Visitors

The R.A.A. advises that motorists who wish to stay in the vicinity of the course during the Centenary Grand Prix and other motor races to be held between Port Elliott and Victor Harbour commencing on 28th December, may stay at a special camp on the Port Elliot showground. This camp has been arranged by Centenary Road Races Ltd., and will be open about December 18 and continue for a fortnight. The charges will be £2/10/ per week, and include three meals daily and a roof. There is a large dining room and sheds for sleeping quarters, but no bedding provided.

Later, reports disclosed that this camp was for men only.

Other preparations included resealing the back straight section of the track, with the dirt surface noted on May 14th, 1936, in The Advertiser as being of particularly poor state after recent bad weather, although the remaining two-thirds of the circuit featured good quality highway-grade bitumen.

One report in the Sporting Globe noted that a white line painted down the centre of the road would see slower cars keep left, with faster machines instructed to pass on the right, while oil was spread around the surface to keep dust down.

Interestingly, it was mentioned in the press in the lead-up that arrangements had been made with landowners to allow for continued vehicle access through to Victor Harbor and Port Elliot via private properties during the meet, with maps showing bypasses around the circuit.

The action over the festival included a Senior Motorcycle TT (up to 500cc), a Junior TT (up to 350cc), a Lightweight TT (up to 250cc), and a Sidecar TT, with cars also invited to contest a 50-mile handicap.

The main event was open to “all factory-built and catalogued racing cars and to all factory-built and catalogued sports cars, irrespective of engine capacity,” providing access to a wide range of machinery, with other specials also considered.

Entry fees were somewhat steep at £2/2/ for both entry and then acceptance, which, adjusted for inflation to today’s money, would be around $450 for each starter.

That said, the total AGP prize pool came to £415 ($45,000), which saw the winner go home with £200 ($21,500) and The Advertiser Gold Trophy, valued at £50 ($5,400).

Cash was paid out down to sixth place, who earned £5 ($540).

The Advertiser, 28/12/36

The Grand Prix proved to be a thorough battle of attrition.

Contested over a distance of 240 miles/386km, a total of 17 of the 29 starters failed to make the chequered flag.

The race was ultimately won by pre-event favourite Les Murphy, who overcame a handicap of 40 minutes to claim honours aboard his MG P-Type, ten minutes clear of the field after nearly four hours of largely incident-free racing.

In a move that would raise the ire of modern time-certain finish haters, the race was stopped 15 minutes after the first three finishes crossed the line, putting two tail markers out of their misery, although the last-place finisher was some 33 minutes off the pace after their final circuit.

The ultimate lap record for the track was set by Tom Peters in a magnificent Bugatti Type 37A in a time of 5min 47seconds at an average speed of 130km/h, with the quickest cars noted as having top speeds of around 175km/h, which was swift motoring considering the condition of the road and the capabilities of the skinny tyres.

At the other end of the speed charts, some of the smaller cars in the field were said only to have a terminal velocity of around 135km/h, which would have been a crippling handicap on the seemingly never-ending straights.

Ultimately, racing at Victor Harbor was a one-and-done deal, never to be repeated.

The Mail, 26/12/34, and News 30/12/36

The Herald, 10/11/36 and Sporting Globe 9/12/36

The Circuit, Then and Now

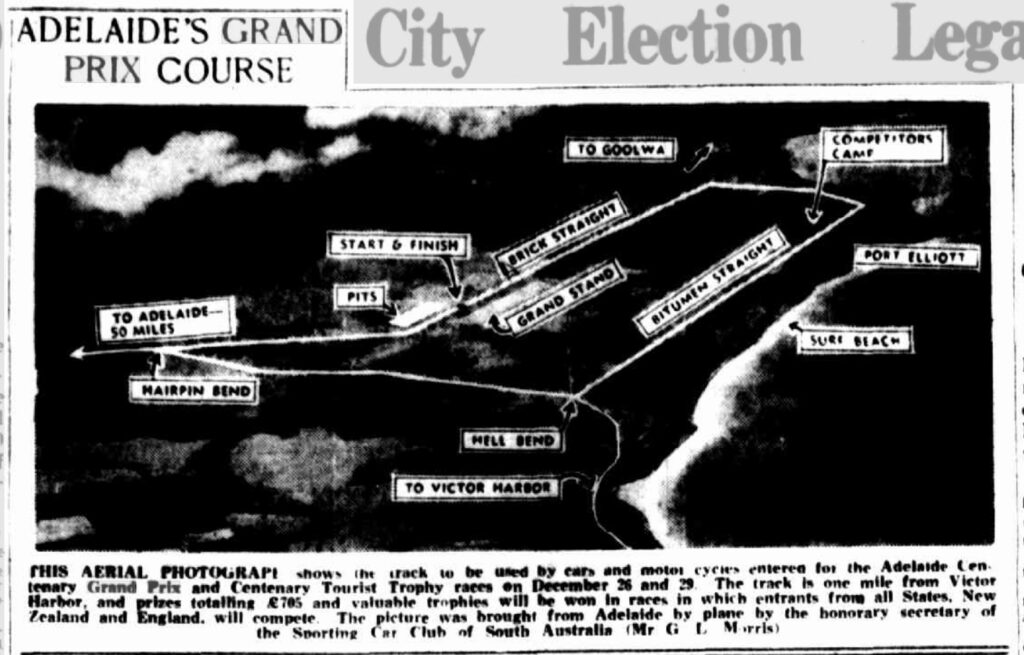

It was an immense layout, measuring some 12.55km long, much of that foot hard to the floor on two massive straights that measure a little over and under 4km a piece – keep in mind, the modern shortened Conrod Straight is 1.3km long, Victor Harbor represented a lot of straight-line motoring!

The lap started on the Waterport Road back straight and hooked clockwise.

The opening straight was known as Brick Kilns, or simply Brick, referring to the facility that used to sit on the corner of Heyson Road.

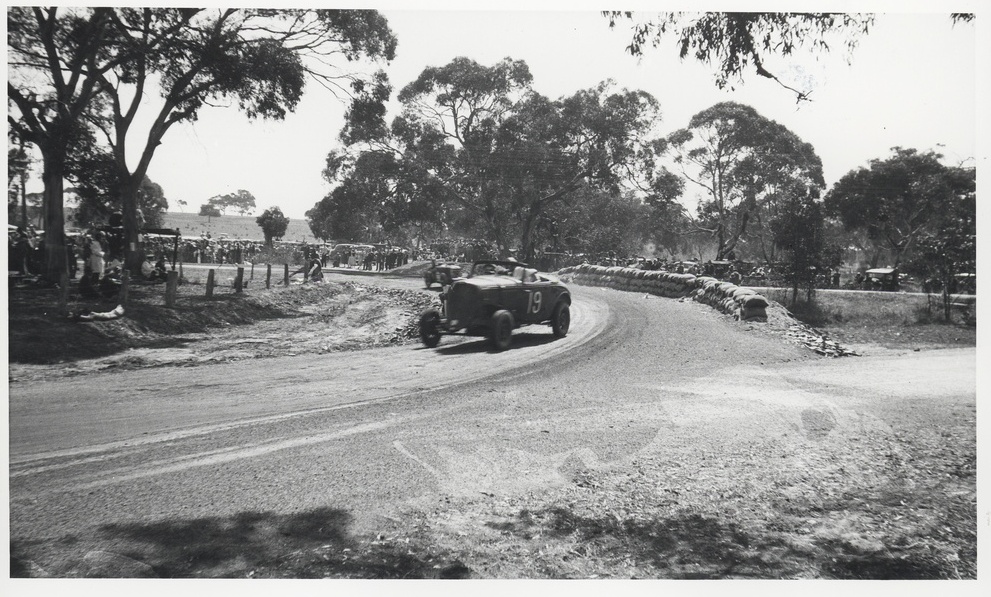

The 28-foot wide track rose over crests before the better than 90-degree hairpin onto Port Elliot Road at the aptly named Seaview Corner.

The road then gently curved through a pair of bends before blasting through what is now the business district of Port Elliot, which, during the event, had wire fences erected to keep spectators off the racing surface.

Over another significant crest, the track rode the valley floor along Chiton Straight (denoting the suburb the road bisected and the location of the modern-day mural, as depicted in the header image), passing over what was described as a ‘humpback bridge’ before rising up to meet the modern-day Bunnings Warehouse.

It is noted that before the meeting, a lot of the undulations on this stretch of track were ironed out by engineers.

The circuit flicked right through ‘Hell Bend’ at the location of the present-day On the Run service station and roundabout before taking on perhaps the most interesting part of the circuit along Adelaide Road.

With reasonable elevation in play, the track swept left and right, before finally descending into what is still open countryside today, and the long straight shot into the hairpin that returned cars onto Waterport Road.

Back at the time of the event, this tight right, named after the nearby Nangawooka Flora Reserve, had its angle opened up via a shortcut, which sat just inside the location of the modern-day roundabout, as visible above.

Waterport Road had one final trick – a fast, pucker-inducing left-hand kink near the pits and the grandstand, which would have been close to the most daunting on the circuit.

It was then time for a deep breath, and grip the wheel for another 31 circuits…