The Battle of Bathurst: Publicly Disappointed

The 1998 AMP Bathurst 1000 will go down in the history books as one of the greatest Great Races of all time.

However, outside of the blockbuster racing, that long weekend in October failed to deliver – crowds weren’t engaged, and neither were the manufacturers or global Super Touring competitors.

In the opening three legs of this deep dive into the Battle of Bathurst, we looked at the formation of V8 Supercars and the subsequent motorsport civil war that broke out in 1997, resulting in the twin 1000km races that year.

Read: Part 1 – The Battle of Bathurst: V8s Vs Super Touring, TV Wars & Council Plays

Read: Part 2 – The Battle of Bathurst: Lawyers Engaged, V8s & Super Tourers Rage War

Read: Part 3 – The Battle of Bathurst: Taking a Financial Bath, Two Bathurst 1000s in one month

Read: Part 5 – The Battle of Bathurst: Death Threats & Regrets, Epilogue to Motorsport’s Civil War

Here in part four, we analyse the series of events that took place throughout 1998, the second year that Super Touring battled V8 Supercars for Bathurst bragging rights.

The Show Must Go On

The Australian Super Touring Championship was rocked in December 1997 by BMW’s announcement that it would be withdrawing its backing from its two-car team, which had been a cornerstone of the championship since its founding in 1994.

The move came after the manufacturer scooped the pool with victory in the Bathurst 1000 in 1997 and registering three titles shared between Tony Longhurst (1994) and Paul Morris (1995 and ’97) – it was a major setback for the fledgling series.

Despite this, the series still had to go on, although with only four true contenders in sprint form: the Audi pair of Brad Jones and Cameron McConville, Jim Richards’ Volvo, and the privateer BMW of Cameron McLean.

In May, the Seven Network secured the ARDC’s contract with the Bathurst City Council to promote the Bathurst 1000 through to 2004, including long-term leases for the ARDC-owned Bathurst facilities, with the event to be run under the “Bathurst 1000 Event Management” banner.

The move would see Seven responsible for all aspects of management, staging, and marketing of the meet. The broadcaster noted in the press that it planned to work closely with the November-scheduled AVESCO event.

The ARDC was retained to supply the officials to run the meeting, which, in essence, allowed the club to ease its financial situation. Auto Action reported the club to be $3 million in debt, including rent arrears to the NSW Government over its Eastern Creek lease.

The club ultimately agreed to the sale of Amaroo Park, which closed in August of that year and was subsequently ploughed into a housing estate.

By June 2000, the Bathurst City Council purchased the ARDC’s remaining Mount Panorama assets, such as the pit buildings.

In a bid to raise grid figures, the Mount Panorama Consortium set about opening the field up to Production Cars, a move which raised the ire of PROCAR’s Ross Palmer, who stated in AA:

“They can’t fill their own grids so they want to play with ours. I can’t believe this… these guys have a bad year, so they immediately want to jump on our bandwagon. I have spent millions promoting the class in Australia, and last year PROCAR ran a very successful endurance race for the cars at Bathurst. Now the Bathurst 1000 wants to come in and cash in on our success without contributing a dollar. Essentially they want to include cars such as a standard Mazda 626 to bolster the Super Touring field. They are out there making cash offers to our drivers without even asking our permission.”

By race time, five production cars would make the grid (and start being lapped within the first three circuits), with the contingent consisting of three Mazda 626s, a Toyota Camry, and a Honda Civic. The field would be further filled by 10 Group S cars from New Zealand.

That production car Camry recently reemerged and became a cult hero for its appearance in the Bathurst 6 Hour.

Later, it was noted that of the $1 million prize purse, $350,000 would be split amongst the TOCA starters, although it was mooted that this would also apply to the Group S entries.

Three days after the Eastern Creek Australian Super Touring round in June, 12 cars converged on Mount Panorama for their media day, with Jim Richards topping the time charts despite a crash at the Cutting early in the day that rearranged the front of his S40.

Also at the media day, a pair of TV commercials were launched, one set to classical music. Alan Gow, TOCA’s worldwide chief, would not comment on the status of international entries.

At one stage, it was floated that the Bathurst 1000 could be the home to the FIA Touring Car World Cup, ditto Kyalami, although, in the end, the concept fizzled out entirely.

Come August, despite the ongoing claims of big international interest, only six BTCC cars featured on the provisional entry list: two Triple Eight Vectras, an independent Honda Accord, two Volvo S40s (which proved to be a combined effort with the local operation), and an independent Renault, who was subbed out come October by the Team Dynamics Nissan, which by race weekend was a quasi works entry.

Once again, the race clashed with the final round of the German championship despite initial assurances that it would be rescheduled, which limited participation from that region, while the invitation for diesel-powered cars was ignored entirely.

Published prizemoney for the event was significantly down, too.

From $300,000 in 1997, the pot in ’98 totalled $123,000, with $50,000 going to the winner, although this figure obviously overlooked any additional subsidies funnelled to competitors.

The 1998 AMP Bathurst 1000

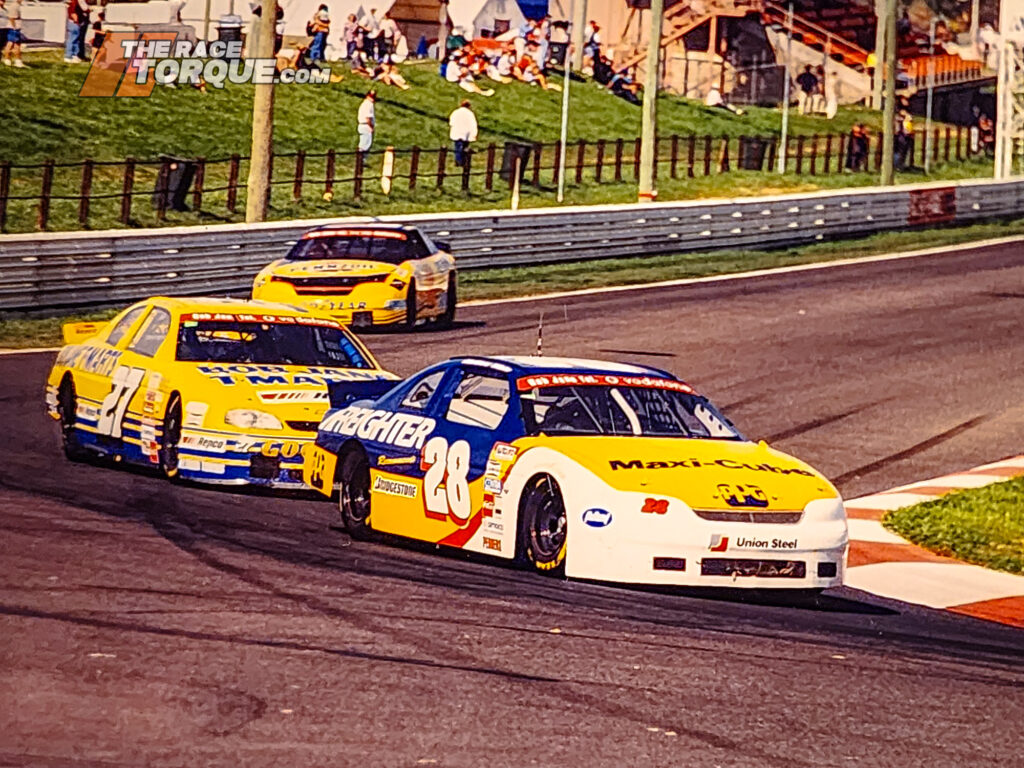

The race itself was one of the most absorbing in the storied history of endurance racing on The Mountain.

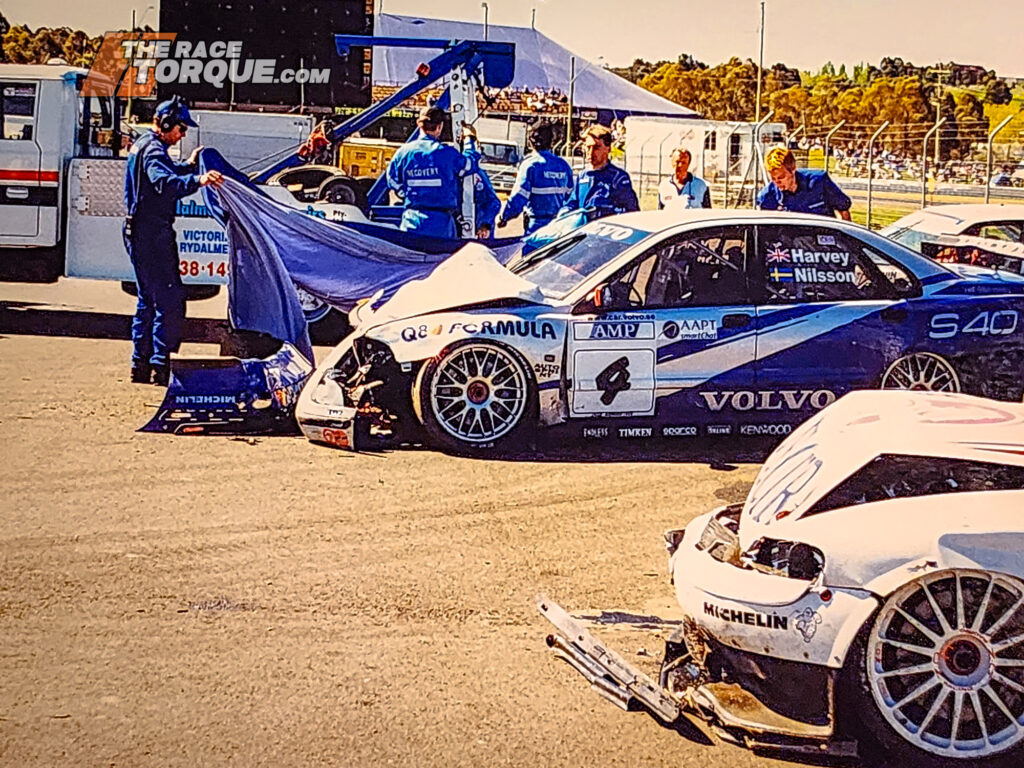

All week, the battle raged between Rickard Rydell/Jim Richards’ Volvo S40 and Steven Richards/Matt Neal’s Nissan Primera.

In the top-ten shootout, Rydell posted one of the track’s all-time best laps—his 2:14.9265sec was ballistic.

While Greg Murphy’s lap of the Gods gapped the field by 1.0962sec, the Swedish florist smoked all and sundry by some 1.4878sec.

On race day, precious little separated the leading Volvo and Nissan, with the battle kicking off from the green light when father was pitted against son.

Nothing split the duo for the entire final stint: Neal was right there with Rydell, and if he hadn’t been baulked by a slower car on the last circuit, he would have been closer than the 1.9975sec final margin.

Brad Jones and Cameron McConville finished third for Audi, one spot ahead of the giant-killing privateer BMW of Cameron McLean/Tony Scott.

While this time around, there were 18 runners at the finish, they weren’t all in great health, with 17 laps spreading the top ten.

The biggest drama in the race occurred on lap 83 when Ian Spurle’s Schedule S Nissan Sentra went full Win Percy 1987 at McPhillamy Park, and smote the inside fence.

Shedding components in the accident, the Audis arrived on the scene in close formation, with the leading car dodging out of the way. This left the Paul Moris/Paul Radisich machine to smash into the debris, which rearranged the underside of the Quattro.

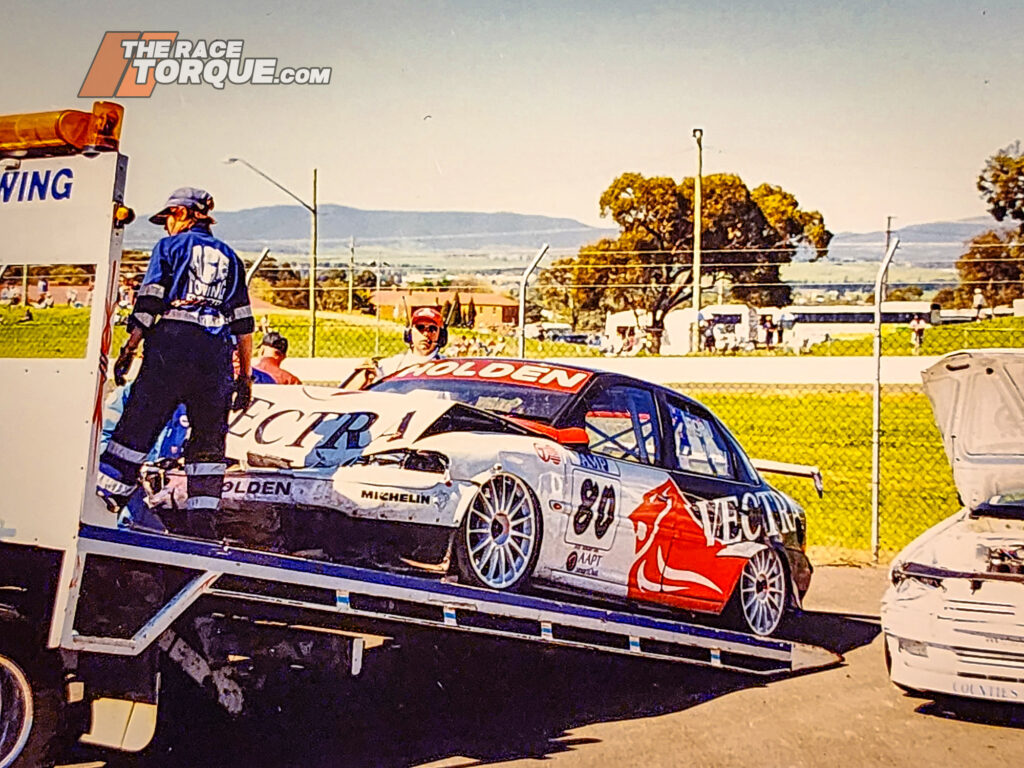

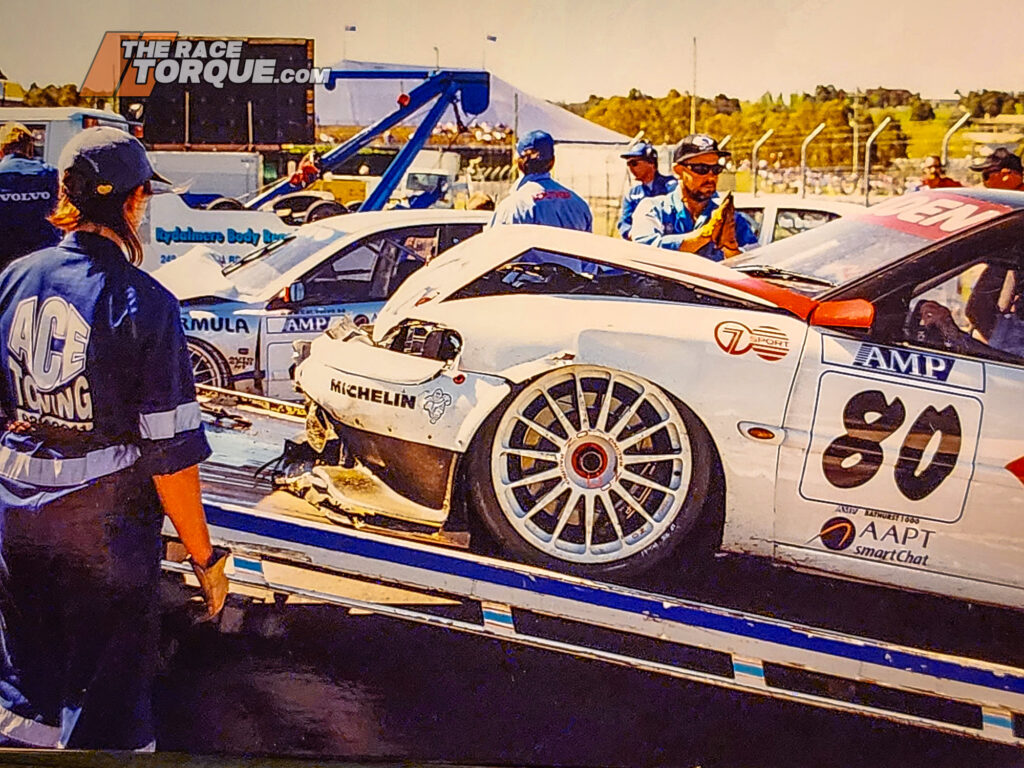

Coating the Esses in oil, Russell Ingall in the Aussie Vectra, Tim Harvey in the second Volvo, and Wayne Wakefield in the Malcolm Rea Carina all arrived on the scene in full flight and left on tow trucks, with Harvey taking a particularly nasty lick.

Ingall was scathing of the “peanut” in the Nissan post-crash – “There are multi-million-dollar teams here, some of the best in the world, and they put shit cars in just to boost the grid for TV. That car took out three possible winners.”

Once again, another lowlight came from the Triple 8 pits, which this time burst alight after a botched refuelling stop early when Derek Warwick pulled away too soon after a service.

Post-race, the official results were once again delayed in the steward’s office, with the second-place outfit protesting the winning Volvo for allegedly passing it under yellows on lap 53.

The claim was thrown out when it was revealed the move occurred on the pit entry road, as distinct from the race track proper.

It was clear that the event needed something, and it was more manufacturer involvement—privateers were great, but they didn’t add to the conversation at the front of the race.

The entry lacked depth – there was a 42sec spread over the field in qualifying, while the time separating the top ten made it the least competitive since the mid-1970s.

The European arrivals had failed to materialise en masse, which was to the detriment of the show.

Pre-event, a crowd of 20-25,000 was expected, with pre-sales up 300 per cent year on year, however, officially, a race day crowd of 16,000 was announced come Sunday evening.

Contemporary press published that figure with scepticism, and the all-important TV ratings were also noted as being poor—between 8.7 in Perth and 13.2 in Sydney. Motorsport News noted that signage sales around the circuit were down.

Despite the vehicles being a good representation of those driven on the road, Super Tourers in five seasons failed to capture the imagination of the competitor base or fans alike—the multi-million-dollar factory-backed crash and bash of the BTCC with their disposable race cars wasn’t a reality Downunder.

Cars are one thing, but stars are another, and they were all racing at Mount Panorama in mid-November.

The Super Touring event also failed to deliver on innovation or outside draws to keep spectators engaged.

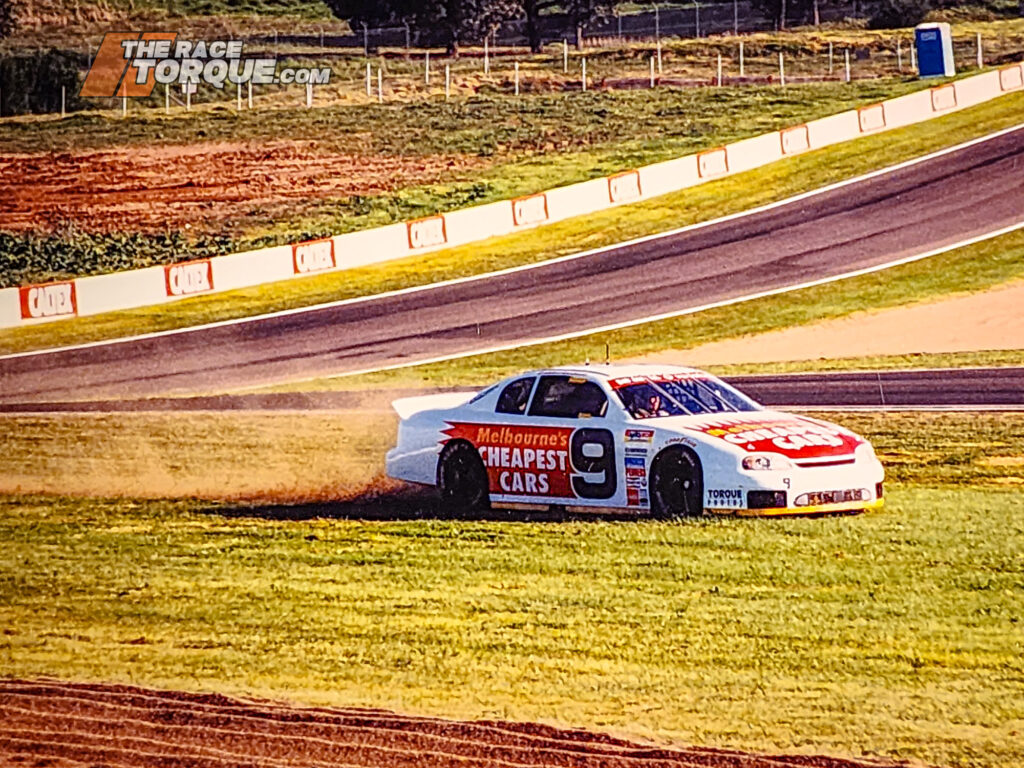

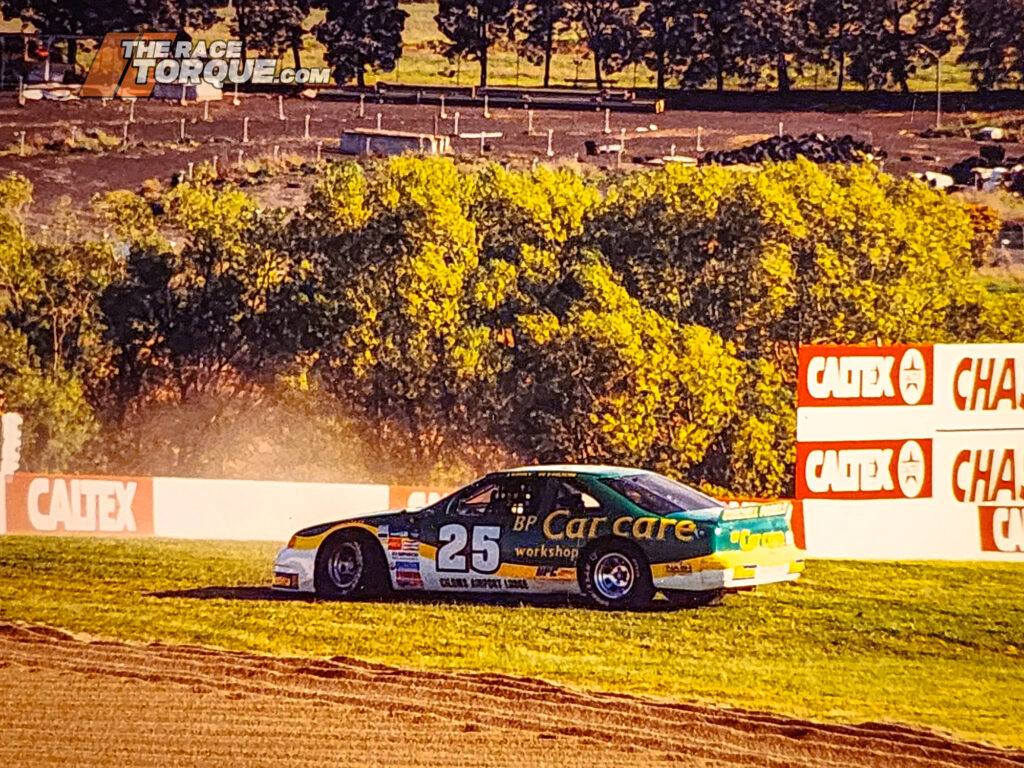

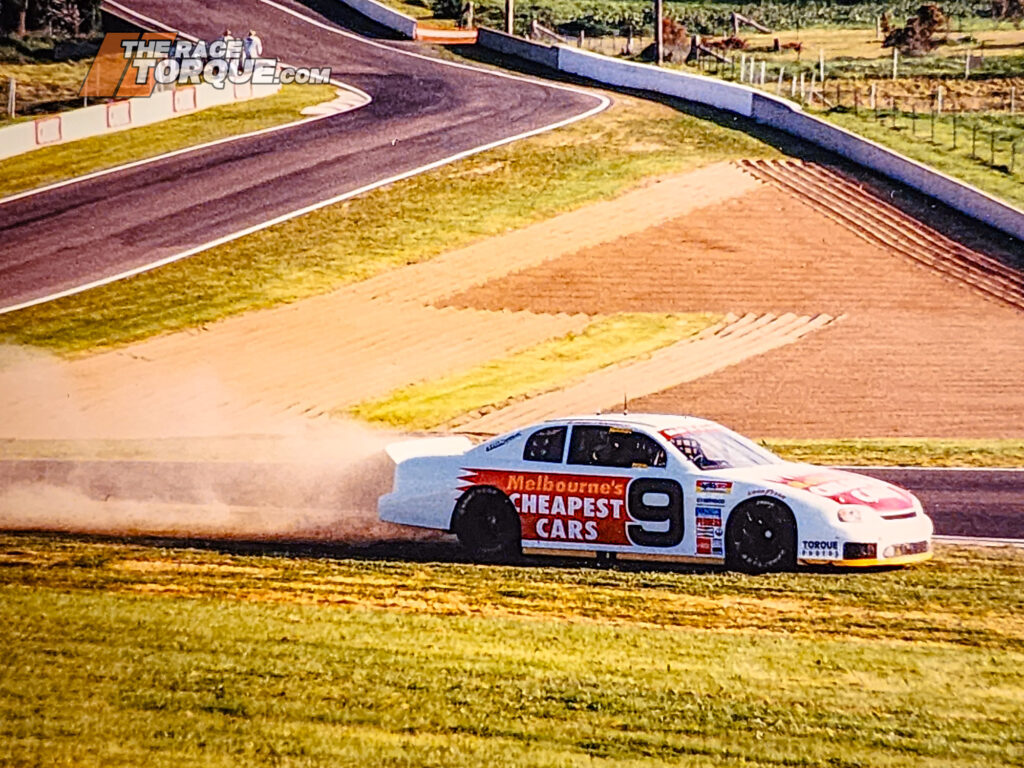

On the undercard, a 16-lap NASCAR race on Saturday afternoon saw 12 cars take to the track. Russell Ingall was one of the few cars not to wobble off the circuit at the end of Conrod Straight as the cumbersome stockcars tried to slow down from a terminal velocity in excess of 300km/h.

By 1998, NASCAR in Australia was on the outer, and racing on The Mountain wasn’t enough to revive the category, which faded away from the Thunderdome following the 1999/’00 season.

Elsewhere in the preliminaries, a race exclusively for Austin Healeys was run, while the Porsche Challenge mixed an interesting pack together, although they were lapping slower than the production cars of modern times.

That 1998 program followed on from an entrée serving of Group N, Porsche Challenge and Commodore Cup in 1997.

Outside factors tugging at the attendance and attention of the audience on that first weekend in October 1998 once again included the Australian Motorcycle Grand Prix at Phillip Island, which was won by Mick Doohan, and the Federal Election, as contested on Saturday, although a polling station was located at the circuit.

Greg Eaton from the Mount Panorama Consortium told AA:

“It is a matter of now addressing what combination and what level of entertainment, promotion and television package is going to make the AMP Bathurst 1000 work. I think some long hard thinking is about to take place. I have to find a new market and that is something I believe we have achieved this year. We now have to build on it and get the mix right.”

Eaton noted to MN:

“I would be lying if I said I wasn’t a little disappointed, but I feel we definitely turned the event around in terms of where we were aiming the event. Our ratings in our key demographics, men under 35, were strong, and they were strong in our sponsor’s key target. The ratings prove that there is a strong audience for motor racing and having two big events on the same day splits it.”

In the same story, Kelvin O’Reilly from TOCA Australia noted:

“We would like to see the biggest crowd you can get there. Outwardly, it wasn’t that big and that’s disappointing. If it had been TOCA arranging the marketing and advertising, we would be in a position to express a public opinion about the outcome. While there are two Bathursts, many people will choose to go to one only. Not many go to both races. People who go to Super Touring events aren’t going to go without a shower for a week or hang their washing on a fence. The town was fully booked out, which leaves few places for people to stay. Most would not stay on The Mountain or act like people out of ‘Deliverance’.”

Later in AA, Cochrane replied:

“What really annoys me is the elitism they (TOCA Australia) keep shoving down everyone’s throat. Quite frankly, I think it’s disgraceful. What I don’t admire, and I get very annoyed, is when they continually have digs at our fans, using words like ‘people out of Deliverance’ and ‘the drunken mob up on the hill’. Quite frankly, I find it disgraceful to use those sorts of references towards our fan base.”

Later, responding to reports in The Australian newspaper regarding losses of up to $5 million for the event, and that Super Touring was on shaky ground, Eaton noted to AA:

“That figure (the $5mil loss) is the third figure I have read in the last week. It (the figure) is a confidential matter between promoters and organisers of motor racing events. I doubt that any business in Australia would be in business too long if they couldn’t arrest any loss figures. We have been given the task to revitalize the existing AMP Bathurst 1000 and put it back on a profitable grounding, and I am confident we should be able to do that.”

Holden, who backed the Vectra entry of Ingall and Murphy, largely dismissed the prospect of running a Super Touring car in future, describing the effort as “fearfully expensive”, with it doubling the budget required to run a V8 Supercar.

A story in AA quoted Holden Motorsport Manager John Stevenson as saying that a full-spec BTCC car would cost $800,000 ($1.6 million inflation-adjusted). He further noted:

“We would consider another proposition from Vauxhall, 12 months from now, if they wanted to come back. But I think there is also a bit of pressure required on Channel Seven – if they want the race to continue properly – they have to make a serious investment in it. Seven has to do two things: they have to come up with a package which ensures more teams come from overseas, and they have to make sure it’s a Two-Litre race and not stack the back half of the field with cars that have a huge performance differential. It doesn’t do the race any favours and it also has real safety implications.”

By the end of the year, TOCA Australia was open to the concept of Junior Tourers running on the series’ undercard, a concept that gained momentum to the point where the V8 machinery was seen as the way to prop up fields in the 1000.

More on that in part five…

The FAI 1000 Classic

Now in November, the V8 Supercars race had some clear air to run in, away from the first weekend in October and the maiden late-season run by the Gold Coast Indy.

Mark Skaife and Craig Lowndes in the lead HRT car were looking like the combo to beat, especially after Skaife smashed out the first sub-2:10sec lap ever by a touring car in the top-ten shootout.

Come race day, the Stone Brothers snookered the field from 15th on the grid, following Jason Bright’s early weekend crash.

Combining with Steven Richards, the pair pitted early and ran off strategy, setting off a generation of tacticians who have made opportune early stops in the subsequent races on The Mountain.

It was a breakthrough win for the Blue Oval as well, who had gone winless since the John Bowe/Dick Johnson heroics in 1994.

Second, and some 10 seconds adrift, was the perpetual Bathurst front-running combination of Larry Perkins and Russell Ingall, who just held on from the GRM combo of Jason Bargwanna and Jim Richards, with Bargwanna making amends for his warm-up faux pas from a year earlier.

The biggest talking point of the race came on lap 58, when five cars were eliminated in a horror pile-up at Forrest’s Elbow.

The officials placed the blame on Greg Crick, who with Dean Crosswell, was disqualified post-race. To this day, Crick pleads his innocence in the matter.

In the end, 46 cars made it to race day, a record at the time for V8s in the 1000, with 20 greeting the chequered flag.

Channel Ten went all-out for the race, with a 67-camera production (up from 39 in 1997) for its 15 hours of coverage. An innovation was its Carcam, which flew on a wire down pit straight at speeds of up to 120km/h.

And that coverage worked a treat, with Cochrane trumpeting its resulting stats in AA:

“Corporate support was up 100 per cent on the previous year, and we’ve just topped it off with our average TV ratings going up over last year and our peak ratings in the mid-20s. We hit 24 in Melbourne and 25 in Brisbane and 21 in Sydney. All day our ratings stayed in the mid to high teens, about 15 and 19, which is getting to 2.5 times the ratings of the Two-Litre race.”

All told, the event attracted an overall crowd of 148,834, a new four-day record, and a race day attendance of 47,144, which was slightly down on 1997 when Brock mania swept the nation, but over 30,000 up on the Super Touring event.

Ticket prices were up year-on-year for both events, but more so for the Super Tourers, where season GA passes sold for $85, a $20 increase.

The total V8 Supercars prize pot tallied $407,000, with $100,000 going to the winning team, while privateers battled over a guaranteed pool of $82,000, with a range of bonuses also on the line.

A War Resulting in an Asterisk

It would be reasonable to say that the 1997 Super Touring 1000 was the zenith of the category in Australia.

Looking beyond the international participation, in terms of sheer numbers, it was a big deal—the championship round leading into Bathurst ’97 drew only 16 entries, the 1000 attracted 30 (including two cars used solely by teams in the preliminaries), and the title rounds that followed at Lakeside (20 cars) and Amaroo (24) were relatively well attended.

The 1998 edition of The Great Race attracted 28 Super Tourers, although that field was further padded out with guests from New Zealand, plus the production car ranks.

While Bathurst brought out the best in Super Touring locally, factors external to Australia, which we will cover in the next installment, conspired against the category.

The Battle of Bathurst was a divisive topic in the media, with party lines clearly drawn on which side of history one was backing.

For instance, The Great Race annuals from Chevron supported the Super Touring meets on the October long weekend, with the 1997 edition providing extended working out in its introduction to justify this position.

Aside from that publication of record, simply reading the general news reporting of the day, the differing tones of voice and spins put on stories in the press painted an insight into the perspective of the authors and publications.

To some, the V8 race was truly an imposter, and it was treated as such.

In more contemporary times, the war has resulted in a mere asterisk in the record books, denoting the oddity that for two years, a pair of Bathurst 1000 races were contested.

Next up in part five: V8 Supercars gets on the front foot to finish the battle, and an epilogue looking back at the players and their modern take on the 1997-’98 war.