The Battle of Bathurst: V8s Vs Super Touring

There may have been no sacred places when civil war broke out in Australian touring car racing, but as it transpired, The Great Race was worth repeating.

On two occasions, our pre-eminent motor race, the 161-lap journey around Mount Panorama, was completed twice in a year, with Super Touring and V8 Supercars each having their own spin on the Bathurst 1000 in 1997 and ’98.

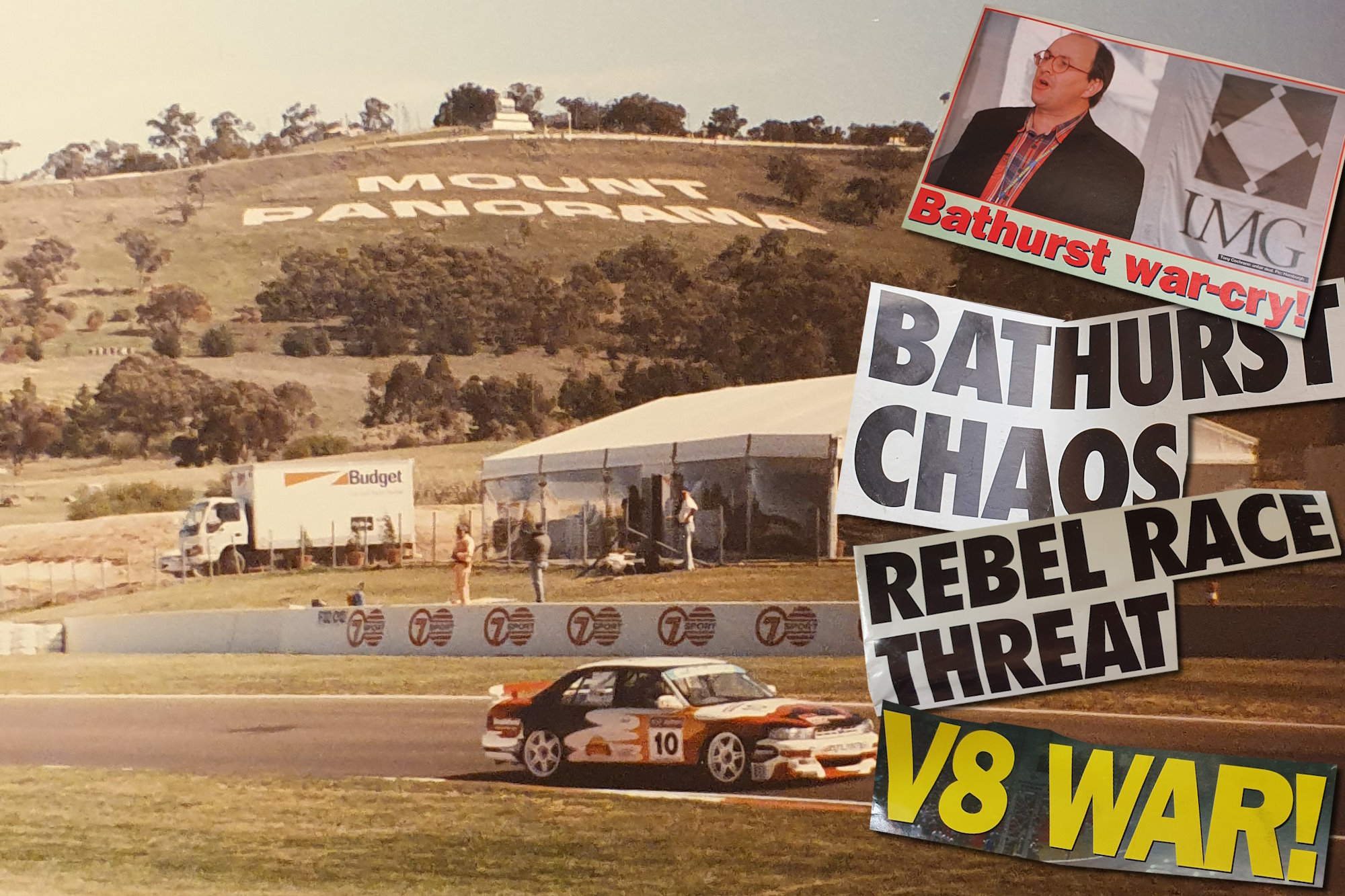

During that time, an incredible war of words played out in the motorsport media as the sport underwent a total transformation.

There were twists, turns, subterfuge and side plots that are remarkable to look back on now after the passage of nearly three decades.

In the end, some protagonists lost the farm, others won the ultimate prize: The Great Race.

Here, in multiple chapters, we take a deep dive into the players and the remarkable plays that shaped an indelible asterisk in the record books of the Bathurst 1000.

Read: Part 2 – The Battle of Bathurst: Lawyers Engaged, V8s & Super Tourers Rage War

Read: Part 3 – The Battle of Bathurst: Taking a Financial Bath, Two Bathurst 1000s in One Month

Read: Part 4 – The Battle of Bathurst: Publicly Disappointed, Epic Race & the Blame Game

Read: Part 5 – The Battle of Bathurst: Death Threats & Regrets, Epilogue to Motorsport’s Civil War

In the Beginning…

By the early 1990s, Group A racing had run its course, with options at the time of its replacement including the British 2-litre formula or a bespoke 5-litre V8 Ford and Holden ruleset that was ultimately landed on for the Australian Touring Car Championship.

Smaller class cars continued to pad out the ATCC fields in 1993, the first year of the big bangers, and this trend continued until the start of 1994, when Steve Ellery made a final appearance in his de-tuned Ford Sierra.

By 1994, the Two-Litre cars were spun off into their own series under the Australian Manufacturers’ Championship banner, which was re-labelled around the world as Super Touring in 1995.

The 1994 season was one of evolution – from a thoroughly stage-managed debut at Eastern Creek to genuine punches thrown at Winton.

Although only seven entries contested the full AMC season, 11 cars entered that year’s Bathurst 1000, the final time the V8 field would be supplemented by other classes.

The category grew in 1995, with Audi joining the factory-backed fight against BMW, and the racing ramped up, too. Exhibit A was the three-wide shenanigans through Lakeside’s fearsome kink between Paul Morris, Brad Jones, and Greg Murphy, above.

Volvo joined the fray, too, with Tony Scott standing out from the crowd in his Besser Brickesque station wagon.

In 1996, the series took another step forward with Peter Brock enlisted by the Volvo squad, this time behind the wheel of a more conventional 850 sedan.

Parked up for Bathurst 1995, the Super Tourers would reappear on the Bathurst 1000 undercard as a standalone support in 1996.

Motorsport at the time, however, was a fragmented beast, with the 1000 standing alone outside any of the championships.

The Great Race was promoted by the Mount Panorama Consortium, a three-way partnership between the Australian Racing Drivers Club (ARDC), the Bathurst City Council and Channel Seven.

In 1995, the Consortium claimed that it was looking to increase race day crowds from an estimated 50,000 to 90,000, focusing on day trippers from Sydney. It also confirmed that Seven had signed on to broadcast the race through to 2004, which seemed like a given since they were a partner in the event.

Enter V8 Supercars

By 1996, the new Five-Litre V8 formula was proving to be incredibly popular. The competition was close, and the formula was right, but it needed more to be elevated from a niche sport to become a mainstream player.

The ATCC rounds that season featured three 20-minute-long races each, and even with the limited racing, host broadcaster Channel Seven was not exactly giving the sport priority scheduling, especially in southern states where AFL was king.

In May, Bob Forbes, Chairman of TEGA, the Touring Car Entrants Group, fronted the media with an ambitious plan to elevate the sport’s professionalism.

The proposal included a promotional blitz, expansion, more manufacturers, improvements to spectator and racer amenities at tracks, circuits were to pitch for hosting rights, and the sport was to establish a full-time office and leadership team.

Forbes noted the need for a better TV deal – the increased exposure would raise the tide for all boats, with sponsorship dollars flowing more freely to competitors.

Formulating calendars and dealing with circuit owners were serious issues for the sport at the time, with the different venues sometimes banding together to best serve their own interests.

The roots of TEGA can be traced to 1988 and the first iteration of a teams’ association – Touring Car International, which for a time was also known as ATCEA, the Australian Touring Car Entrants Association.

These collaborations plodded along, largely funded by DJR and Gibson Motorsport, and didn’t necessarily rock the boat.

V8 Sleuth recently uncovered a story where Advantage International, a player in the fourth chapter of this story, proposed a similar revolution in 1989.

TEGA proved to be more successful in organising the troops when it was formed in 1994; however, the sport remained all over the shop, especially in terms of the ownership rights of its associated properties.

Tony Cochrane, IMG’s Senior International Vice-President Australasia, first met with Neil Crompton and Bob Forbes in Sydney, then met further players at events in early 1996 before he finally presented a white paper to the team owners at HSV’s offices in Melbourne, which ultimately set the wheels in motion for change.

Come September, the relatively amateur world of Australian motorsport changed forever with the announcement of IMG entering the sport, and with it came an ambitious set of goals.

At the heart of the announcement was locking in a better TV deal for the class and better timeslots, which aimed to grow audiences exponentially from the 600,000 mark into the millions worldwide.

It wasn’t hard—in the AFL-mad southern states, Seven’s touring car coverage was regularly bumped to late on Sunday nights, making it difficult for casual viewers to access.

Outside of plans to expand into Asia, New Zealand, and South Africa and moves to improve fan experience and promote the series as a whole, an underlying principle was the company’s CART-styled franchise system, which provided teams with a stake in the game while also guaranteeing participation.

The franchise system evolved over the decades, and at times, the licenses traded for up to $2 million apiece.

Cochrane was the face of the new venture, and he was familiar with the CART business model —the Queensland Government had charged him with turning around the Gold Coast Indy meet from its loss-making ways.

As chief executive at the event, he had hands-on experience in the motorsport world, while he also had earlier performed a rescue mission at the Australian Motorcycle Grand Prix at Eastern Creek.

The united front was the culmination of six months of negotiations, with IMG noted as backing the project to the tune of $250,000.

The new company was set to be a joint venture combining IMG, TEGA, and CAMS’ commercial arm, the Australian Motorsport Commission (AMSC).

After years of messy dealings and suboptimal outcomes for competitors, this deck shuffling added the marketing know-how the series couldn’t achieve within its own ranks.

Straight off the bat at the press conference convened in the Sandown 500 paddock, Cochrane proclaimed that Bathurst wasn’t a sacred site.

Auto Action subsequently reported:

“Bathurst is a very unfair deal for TEGA and that is going to be looked at. It’s just ridiculous these guys go up there, with all their investment, for $150,000 in prizemoney, or whatever it is ($300,000), while the Consortium splits a couple of million. That’s an example of an unfair deal. We’d run it (the Australian 1000) on the Labor Day weekend at wherever… (but) we may sit down with them (the Consortium) and they say ‘We really want to include you guys, now how can we work together?’ and bang, bang, bang, we’re fine. Take the V8 touring cars off the Mountain in October and they have got no show. Fact. These guys are the show. People want to see V8 touring cars on the Mountain, with the stars driving them. All I am saying is that they (the Consortium) have put together a most unusual contract, with the track, a TV company and another independent organising body, but not with a sports star.”

Let the Politics Begin

It was a time of upheaval in sports: Australian Rugby League had its Super League war, while overseas, the debris trail left by the CART/IRL split had barely hit the asphalt.

Australian motorsport was about to have its battle of Bathurst.

By the first week of November 1996, the V8 Supercars name was locked in to replace the clunkiness of the various V8/Five-Litre touring cars/Group A/Australian Touring Car Championship titles, with the company behind the joint venture to be known as AVESCO.

Before serious discussions with circuit promoters about forming a 1997 calendar kicked off, IMG set about locking in TV deals both domestically and internationally.

At one stage, Channel Nine was mooted in the press as having the front running; ultimately, the deal landed with Ten, with a contract through to 2006, following in the footsteps of its five-year agreement to broadcast the Sandown 500.

Priority race broadcast timeslots at 3 to 5pm nationally on Sunday afternoons would be supported on off-weekends by what was to become RPM.

The V8 Supercars agreement with Ten was in addition to its commitments to 500cc racing, World Superbikes, Indycar, the Australian Super Touring Championship, the Australian Rally Championship and the British Touring Car Championship.

The network was truly the home of motorsport.

At the time of confirmation, Ten was going to pump in over $3 million per year in production costs and pay a “seven-figure” amount (later quoted as $1.2 million) consisting of cash and contra in the form of in-broadcast advertising space to be on-sold by AVESCO, who also, at the time of release, had already sold international rights to the tune of $550,000.

In short order, IMG had made V8 Supercars a lucrative venture.

However, the deal with Ten was entirely at odds with the decade-long contract between the Mount Panorama Consortium and Seven, the network that had always covered The Great Race and had, in essence, simply been granted the ATCC rights since claiming them in 1985.

While prizemoney and payments to competitors were at one time a major stumbling block, the battleground quickly switched to one of TV rights, with a key stipulation in Ten’s contract being an endurance race – whether it was at Bathurst or elsewhere.

The day following the V8 Supercars brand unveiling, the Consortium issued a press release stating that it planned to invite V8s to the 1997 AMP Bathurst 1000 and was seeking to meet with TEGA.

The release deliberately excluded IMG from the invitation while discounting Super Touring as a serious option for the race.

Cochrane noted his surprise that the invitation came in the form of a press release rather than a phone call, while Consortium Administrator Greg Eaton, a 15-year veteran of Channel Seven’s employ, noted that increased prize money would depend on improved entry numbers.

These were the first public bullets fired in the fight.

To the side, TOCA Australia, the controlling body of Super Touring, was noted as taking exception to the new V8 Supercars moniker, pointing to the similarities to its own internationally known name.

Curiously, the AMSC, a partner in the V8 Supercars joint venture, wrote to its other partners that it considered the name unacceptable, a position backed by both CAMS and the FIA.

The AMSC and TOCA weren’t alone in not falling in love with the V8 Supercars title; many in the industry expressed their disdain.

In response, Cochrane asked for suggestions to be put forward – he wasn’t fussed about the title, so long a single name united the sport moving forward.

Some 27 years later, many people would prefer Supercars to add the V8 back into its title.

As the year closed, discussions with the Consortium had come to a stalemate, as Cochrane noted to AA:

“We still have enormous sticking points, we’re not close. But we are trying to do the right thing and keep it open for us to go to the Mountain. They (the Consortium) claim they can’t give us any more money, they can’t drop (teams) entry fees, they can’t do this and that. On the other hand, they’re talking about airfreighting out from England 20-odd Two-Litre cars, which will cost about US $1.2 million! These are the same people that can’t raise prizemoney by $400,000. Channel Seven is no longer part of the (V8) TV deal, and we aren’t going to the Mountain without Ten. Seven aren’t going to promote the sport for the rest of the year, why would we do the right thing by Seven? If we are not going to get a fair deal then we really want to look at something for the long term.”

Alternate venues mooted included Phillip Island and an unnamed international destination.

At one point, the ARDC was keen to open Bathurst entries simply to log booked Group 3A Touring Cars, which would have encompassed non-TEGA affiliated privateers. At the same time, the Consortium considered Super Touring the long-term future of the event, even capable of making an appearance before the year 2000.

A piece by Mike Kable in The Australian about a prospective V8 Supercars race on the streets of the Adelaide Parklands was about to change everything, even if it were inadvertently.

The story was described by Cochrane as “Crap, but a fantastic idea,” and within the week, IMG was in discussions with the SA Government.

AA reported that the negotiations were fruitful, while others were entirely dismissive of the notion of a Touring Car-centric street race, but in April 1999, the Sensational Adelaide 500 came to life.

The Great Christmas Grift

By Christmas 1996, two Bathurst 1000 races in 1997 were set in stone following the breakdown of discussions between AVESCO and the Consortium. This was achieved thanks to an incredible piece of manoeuvering that blindsided two Bathurst mainstays, with AVESCO using the prospect of a replacement race in Adelaide as the perfect bargaining chip.

Bypassing the Consortium, AVESCO struck a deal directly with the Bathurst City Council to run a second event on October 19, a fortnight after the traditional long weekend date.

It was a stunning move by the Council, which had been one of the Mount Panorama Consortium’s three prongs until that point.

Subsequently, the ARDC noted that the relationship was “ruined.”

For the Council, it was a win, with Bathurst getting a double dip of tourist dollars in the month of October – their racetrack was being underutilised, and any extra events provided a massive boost for the regional centre.

Motorsport News reported on the sequence of events that saw the Council defect:

December 16: All major V8 teams (excluding HRT) signed a document to state they would skip Bathurst in favour of an endurance race on the former AGP track in Adelaide.

December 18: The Council confirms the deal with AVESCO.

December 19: The deal was ratified at the TEGA AGM, where all executives were re-elected.

December 20: The Australian 1000 was announced to the media in Melbourne.

December 21: The ARDC held an emergency meeting, with the Super Touring route seen as the most likely outcome.

December 23: Channel 7 backed the ARDC event.

Items still had to be ratified, such as final sign-off by the council, track signage and event permit, which may have been seen as a stumbling block after CAMS’ Interim Chief Executive Tim Schenken stated that no permits would be issued within three weeks of the traditional Sandown and Bathurst dates.

The ARDC noted that it indeed owned the pit complex and corporate suites, but were contractually obliged to rent them via the council to another promoter if required once per year – when that clause was drafted, it was never intended to be to the detriment of its own event.

Ultimately, that lease figure would come in at a paltry $4,000, while the makeup of the V8 event’s stakeholders landed with 65 per cent controlled by IMG, 25 per cent by the Council, and 10 per cent by AVESCO.

In the meantime, the ARDC swooped in to register AVESCO Pty Ltd, an acronym standing for the ARDC Vee Eight Sports Car Company, while ongoing questions were raised concerning the AMSC’s involvement in the V8 Supercars joint venture, pointing to potential conflicts of interest.

Earlier, Ron Meatchem, TEGA Chairman, noted:

“If the AMSC want to pull out of AVESCO, that’s their business, but they’re pulling out of making quite a lot of money – they’re a shareholder.”

In essence, for CAMS, its involvement in AVESCO through the AMSC was seen as a blueprint for its future category management agreements.

By the middle of January, no deal had been confirmed for Super Tourers to compete in Bathurst one. The ARDC was cautious after the club was burned badly financially by the 1987 WTCC fracas, while TOCA had yet to unveil a calendar for their season.

Also, at this time, the Australian Vee Eight Supercar Company Ltd, or AVESCO Ltd, was confirmed, with Meatchem noting the ARDC’s application as “frivolous.”