The Bathurst Riots: A History of Conflict

Many facets add to the legend of Mount Panorama: the impossible circuit layout, the incredible races, and the gladiators who go into battle. However, none of these factors would count for anything if it weren’t for the devoted fans who line the incredible ribbon of asphalt. Over generations, the top of The Mountain grew a reputation as a truly wild frontier, and centre to this was when anarchy took charge in the early 1980s in the series of Easter Motorcycle riots.

Police provocation, bad behaviour and sensationalist media reporting conspired to ruin one of the biggest motorcycle events in the world.

Here, in multiple parts, we will examine the players and the mechanisms of the battles between the punters, the police and the press in what was a complex melting pot that had been decades in the making.

Further Reading:

Part 2 – The Bathurst Riots: The 1980s War

Part 3 – The Bathurst Riots: The BYOG Ban

A Bathurst Tradition

Motorsport in the Bathurst region at Easter has been a fixture since the 1920s.

After formative meets on the district’s backroads, racing moved to the insane Vale Circuit in 1931 before landing at Mount Panorama in Easter 1938, with that inaugural meet playing host to both the car and motorcycles.

Outside of war, through to 1973, cars and bikes shared the Easter bill; however, when the four-wheel set focused its efforts on the October long weekend and the 1000km race, motorcycles took sole ownership of Easter action on the hill.

While the violence of the 1980s is at the forefront of recollections, conflict between racing patrons and authority had been brewing for some time.

The first reported significant battle between police and racegoers came back in 1960 at the Kings Parade Park, fittingly across the road from the Bathurst Courthouse, a venue that was central to this ongoing story in the subsequent decades.

Between then and 1979, a total of five police and media-defined riots occurred around the Easter race meets in 1960, ’65, ’66, ’72 and ‘76, with police operations moving to the top of The Mountain in 1975 before a permanent compound was constructed in 1979 to assist in maintaining public order.

However, the new base only intensified issues, with its presence institutionalising the hostilities.

By the 1980s, the conflicts elevated in their ferocity, becoming nationwide front-page headlines, with events in 1983 an ultimate tipping point – that year, 163 were arrested, and 93 police were injured in an utter bloodbath.

All told, in 28 years from 1960, 2,868 arrests were made in association with the Easter race meet.

Not everyone camping on top of the hill was involved in the conflicts; protagonists were in the minority, many campers kept to themselves, and others simply watched on – often, it appears that everyday race fans were caught in the crosshairs of the media and the police.

Policing style was forever a talking point.

From claims of outright aggression to passively lighting the spark, the motorcycle set was an easy target.

At times, motorcyclists were pulled over three times en route to the circuit; at others, people were booked for ridiculous things like having mud splashes on their number plates.

The deployment of the Tactical Response Group riot squad was a contentious issue, too.

While some police tactics were questioned, in years of no rioting, such as 1982 and ’84, by ignoring the obvious baiting from the crowd, conflict was bypassed.

Bathurst, as a regional centre, was also caught in a tough situation. The events at Mount Panorama brought millions of dollars into the town, but at the same time, front-page nationwide stories of riots were terrible for its reputation.

While the tourist dollars were big, the costs associated with policing, hospital treatment and bogging down the court system were also significant.

The media played a part, with later analysis noting that the reporting of the event only served to draw more bad eggs into attending – framing the event as a war with the police, those without an interest in the sport came prepared for battle.

The events on Mount Panorama spawned a series of reports and case studies on the relations between motorcyclists and the police, the police and hardened criminals, the role of the media, and the protagonists’ psychology.

As an example, a report entitled ‘Situational Prevention of Public Disorder at the Australian Motorcycle Grand Prix’ by Arthur Veno and Elizabeth Veno, which ultimately went on to cover the AGP at Phillip Island, noted that one year:

“There were at least three reported occasions, verified by members of the research team, where a member of the media overtly attempted to get spectators to throw missiles at police or the police station for filming. In one case, a television crew actually offered to pay for such actions.”

While much has been written from the perspectives of the various participants in the battles, here we break down that incredible series of events as it played out, and the reaction that changed the face of Bathurst forever.

Boys Light Up

Prior to the spotlight shining on Bathurst hooliganism in the 1980s, considerable police attention was paid to events around Easter, with the typical roster of 25 local officers joined by many imported counterparts from the city.

Year after year, reports circulated retelling the ongoing battle between visitors and authority.

Looseness was reported back to the 1930s and the dawn of Mount Panorama.

In 1946, reports circulated of antics downtown when the Easter races rolled into Bathurst. The police at the time were anti-motorsport, and the scuffles were fantastic fodder for the capital city press.

On various counts, including an earlier deadly crash between a competitor and a spectator, the police refused to authorize the 1947 event, which was held in October after the mess was dragged through the court system.

For a second time, the police attempted in court to stop the event from taking place, but they once again lost.

In 1952, there were reports of multiple thefts and vehicles being stripped, while stolen vehicles from Sydney were found dumped in the town during race week.

The next year, the Royal Hotel found itself in court after it was found to be open after hours without permission on Good Friday. The publican noted that it was “to protect his property” because if he hadn’t, the crowds would have “broken the door down.”

At 10:40pm, 56 people were in the bar, with 52 being out-of-town visitors – in those days, much of the party happened in the heart of Bathurst rather than in the campsites on top of the old Bald Hill.

In 1956, it was noted that police had to intervene when a drunken spectator rolled a beer bottle onto the track. In the lead-up, the constabulary carried out an operation to search all attendees of the event, ultimately resulting in only 15 fines.

In 1964, police arrested 70 youths from a wild mob of more than 200, with 37 arrested after they had challenged police to fight outside the police station on the Saturday night of race weekend.

Continued violence petered away when the crowd dispersed away from the city before the car races kicked off on Monday.

The youths called to police to “come out and fight.” Bathurst’s two burliest police officers, Det. Sgt. G. Powell and Det. Const. G. Williamson, and three other constables took up the challenge. When the police emerged from the police station, however, the youths scattered. (Elsewhere), an explosion of gelignite rocked the town on Saturday night, but no damage was caused.

The Canberra Times, 31 March 1964

Although not necessarily a police or ‘bad egg’ issue, in 1965 there was consternation when a spectator drove his car up Conrod Straight in search of a good vantage point. Things were pretty wild in those days…

In 1966, 70 police arrested 176 in a blitz, with a crackdown on vandalism, drunkness, indecency and car stealing.

Only nine of those charged fronted to court with the rest forfeiting their bail.

Of note, Michael Blackwell from Victoria was given a suspended sentence for having explosives in his possession – he had made a hand grenade to give a fright to a man who had overcharged him for motorcycle repairs.

He subsequently lost his nerve and detonated the device outside of the town.

From a wide-ranging motoring crackdown, in 1967, 400 motorists were booked in Bathurst across the Easter weekend.

Come 1968, 130 were charged, with key incidents including a girl being wounded in the head by a rifle bullet and a Post Master General letterbox being blown up by gelignite, scattering debris for 70 yards.

Amongst those arrested were several younger females on charges of being “exposed to moral danger.”

Reporting of these incidents also mentioned the horrible crashes suffered by both John Harvey and Leo Geoghegan, who careened through a fence 40 yards into a paddock before his Lotus hit a tree, ejecting the driver.

In 1969, there was a deadly twist to festivities, with two teenage girls killed when they were thrown from a ute when it overturned near Mount Panorama, resulting in a 20-year-old being charged with manslaughter, while 112 people were arrested associated with the races, which was considered low at the time.

1970 was described as one of the quietest in many years, with 80 police arresting 130 people from the 15,000-strong crowd.

One report from a race fan noted that the: “police were unusually well behaved, and I believe this is the reason the whole weekend seemed to be of a higher standard than in previous years when police were often stupid in their approach to people in town and camping at the track; they caused more trouble than if they had stayed away.”

Meanwhile, in 1972, dire headlines were splashed through the mainstream press, although police admitted to less than 20 arrests.

Long before Dick Johnson hit his rock in 1981, a rider named Gary Coleman took a big tumble in the Esses in 1975 after hitting a rock that rolled down from the spectator area.

The meet ended in acrimony for the motorcycle set, with police stopping everyone while cars were given free passage away from the track.

In 1976, 250 people were arrested, including 60 bikies.

Inspector I. Evans said the confrontation began when about 500 bikies blocked a public road. Later, 300 “wanted to have a go”, and eventually “, about 120 said they wanted to fight”. “Instead of having them advance, we went out and met them”, he said. “We ran towards them and it must have had some effect. They turned to water and started to run”. Police said no injuries had been reported.

The Canberra Times, 19 April 1976

Police said the arrests followed an incident when 120 bikies, most of them from Victoria, threw beer cans filled with gravel at police on Saturday night, surrounding a mobile police station and challenged police to a fight.

The Canberra Times, 20 April 1976

All told, 300 charges were laid, 200 from the events on Saturday night, although in court, 146 people forfeited their bail of $1 each by not appearing.

Following the race, a Molotov cocktail caused several thousand dollars’ worth of damage to the Bathurst Courthouse, with those associated with the race blamed.

Ultimately, $5,300 in fines were dished out, and one man was jailed – Raymond Chalton, 23 of Queanbeyan, who was sentenced to two months for damaging a police vehicle, assaulting a food-bar attendant, and biting a policeman, amongst other issues.

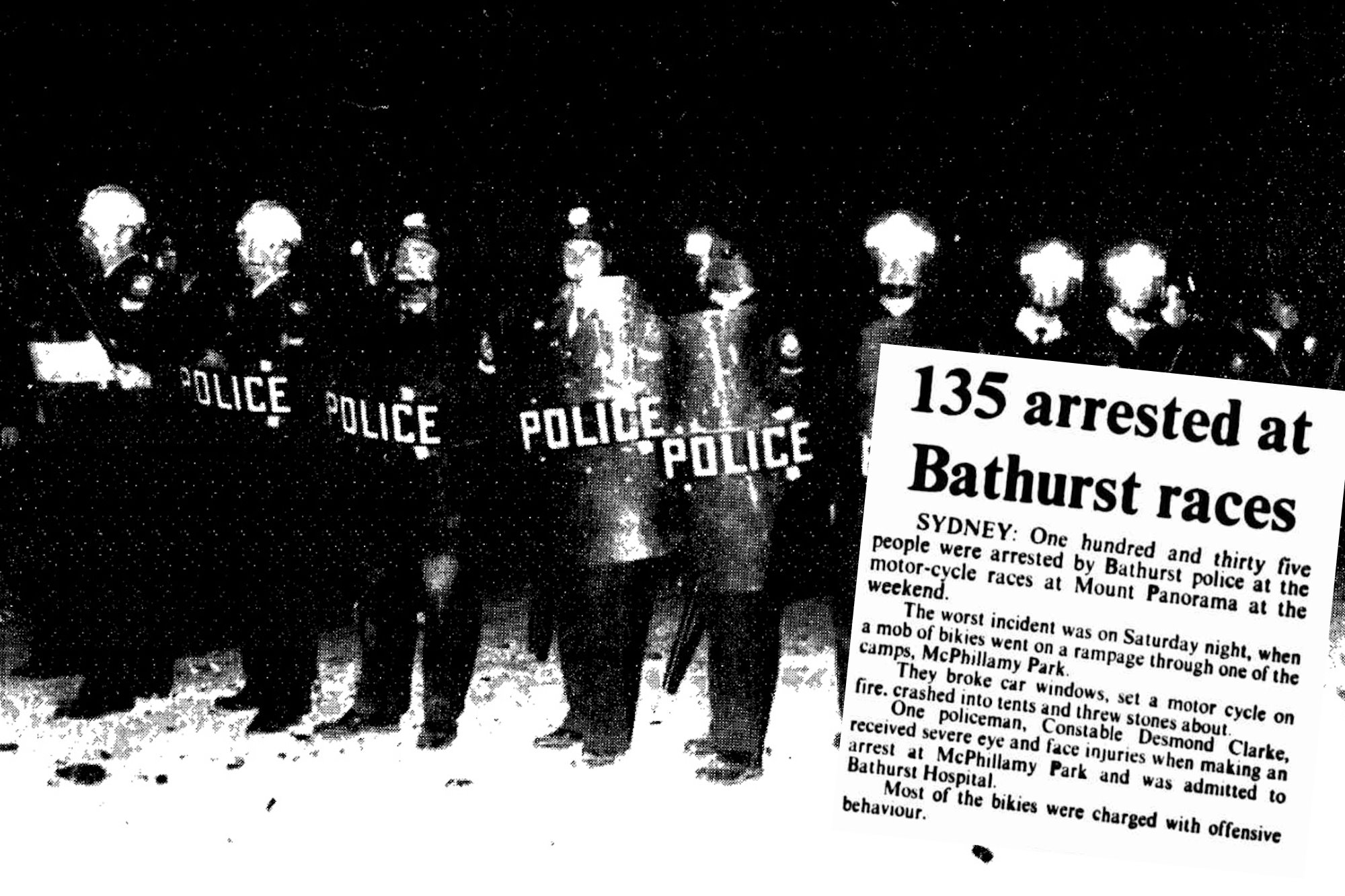

Come 1977, 138 were arrested, with the worst incident seeing a mob go on a rampage through McPhillamy Park, breaking car windows, setting a motorcycle on fire, crashing into tents and throwing stones.

Following the event, a Bathurst magistrate dealt with 32 listed cases in only 40 minutes. The worst offender was Peter Leonard Martin, 23, from Frankston in Victoria, who lost his licence for a year when he was booked going 150km/h.

In 1978, a fleet of buses transported 350 police to Bathurst, with an early arrest coming after police discovered a man at the circuit with a “set of illegal kung-fu fighting sticks”.

The acts of the police were never far from the spotlight.

In 1979, one university student attending the race was arrested by plainclothes police in downtown Bathurst at 9:45am on Sunday morning for putting his foot on a council bench.

He was charged with offensive behaviour and released on $50 bail, after being strongly interrogated at the police station.

Next Up: The 1980s saw conflict truly blow up on The Mountain, with fans, police and media going to war…