Perfectly Preserved: Melbourne’s Original AGP Track

Previously on these pages, we ran a story on Queensland’s 1949 Australian Grand Prix – a meeting where any airfield would do. For that event, an exhaustive search landed on the rural Leyburn triangle of surplus World War II runways, which could easily be converted into a race track.

As it transpires, 12 months earlier, Victoria was faced with a near-identical quandary.

The spiritual home of the AGP on Phillip Island was no longer suitable, while options on the Mornington Peninsula were pie-in-the-sky stuff.

Additionally, the old triangular street circuit in Benalla was also ruled out.

However, a little closer to Melbourne, an option presented itself on the shores of Port Phillip Bay, 20km as the crow flies southwest from the CBD.

State Library of Victoria

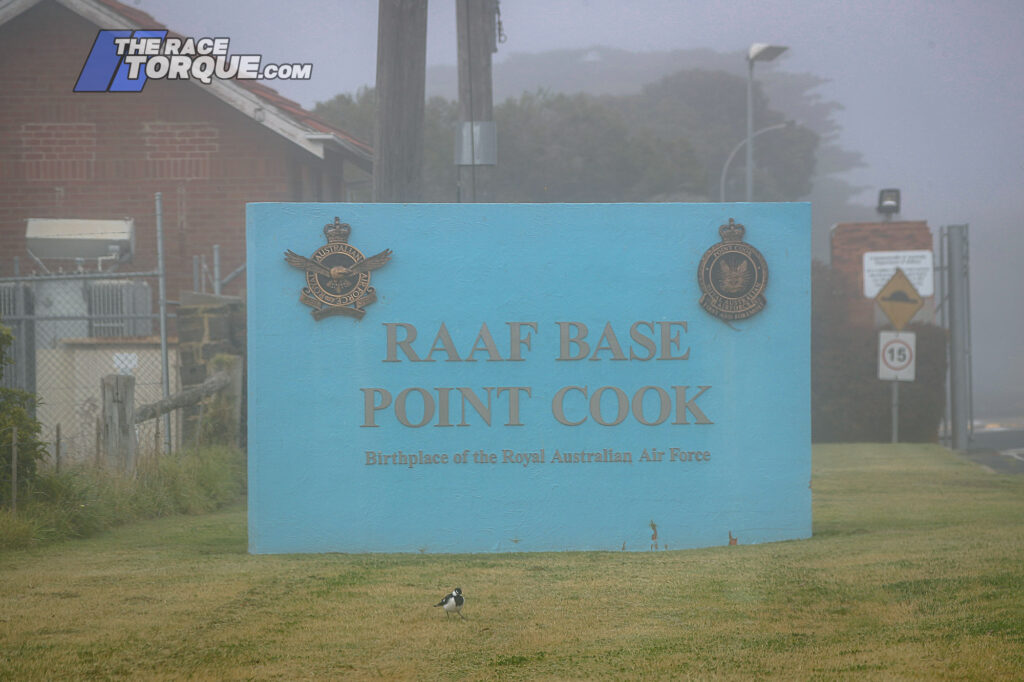

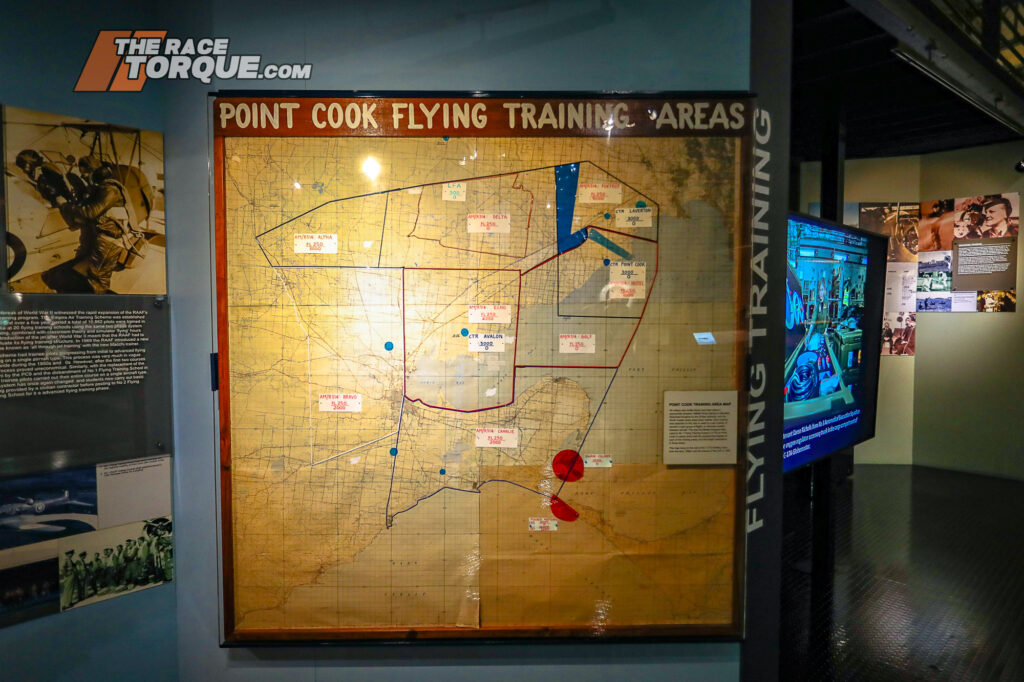

RAAF Base Point Cook

Not only does RAAF Base Point Cook hold a special place in the history of Australian motorsport, it is also one of the most significant airfields in our aviating heritage: it is considered the home of the RAAF, and its continued operation makes it one of the longest continually operational military aerodromes in the world.

The parcel of land was originally purchased by the Australian Government in 1912 and was home to the Central Flying School, which kicked off just after the work commenced to form the Australian military flying corps.

The first flying course at Point Cook started 13 days after the outbreak of World War I.

In 1920, the Australian Air Corps was reformed as an Australian Army Unit, with the Australian Air Force created in March 1921, five months before the service received its Royal prefix from King George V.

Squadrons 1 through 5 were based at Point Cook in 1922, and the airfield remained the only RAAF base until 1925, when Richmond, northwest of Sydney, and nearby Laverton came on stream.

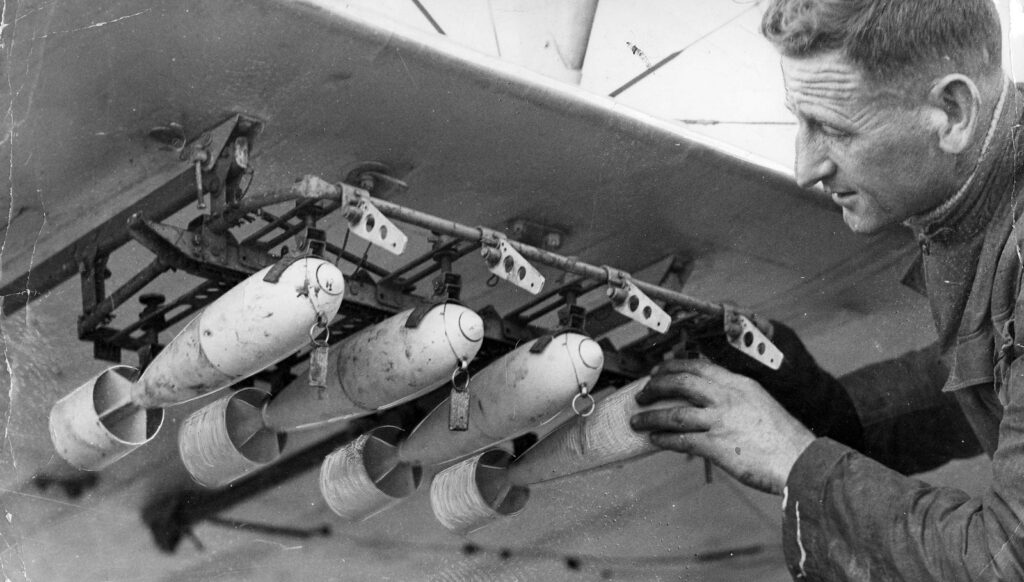

After the declaration of War in September 1939, Point Cook played a crucial role in training programs across a range of disciplines, such as flying, navigation, reconnaissance, signalling, armaments, operations, and instruction.

The base claimed many firsts, such as the first Australian military flight in 1914, the first flight of an Australian-made military craft in 1915, the final destination for the first England to Australia flight in 1919, the start and finish point for Australia’s first aerial circumnavigation in 1924, the first emergency use of a parachute in 1930, plus it played host to the first crop dusting trials in 1939.

Australian Women’s Weekly

The 1948 Australian Grand Prix

Interestingly, despite being the 13th in the series of AGP races, following events at Phillip Island, Victor Harbour, Bathurst, and Loebethal, Point Cook was the first AGP not to be contested on public roads.

With Point Cook, the Light Car Club of Australia had a range of runways and service roads that it could configure to suit the Formula Libre cars of the day.

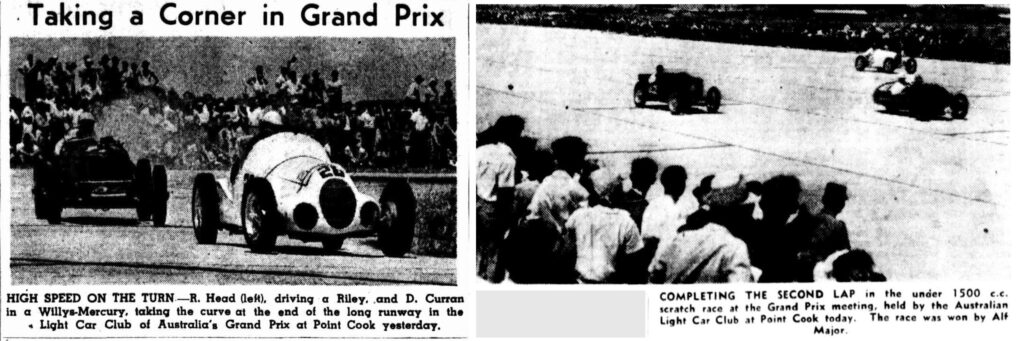

The ultimate course ran anti-clockwise, with the start-finish straight located on the main 1,371m long, 45m wide north-south runway.

At the top end of the airfield, cars hooked left, before a series of sweeping bends brought the competitors past the main line of hangars.

The track then curved around past Runway 04 before a short straight led competitors up to the 90-degree left onto Runway 35.

While pancake flat, the 3.85km layout would remain interesting to this day, and out of sight more entertaining than other circuits of the time, such as Phillip Island or Victor Harbour, which featured miles of never-ending straights.

The event once again proved difficult to access for competitors, with fuel rationing still in full force – some competitors pooled tickets with people along the route south.

Bill Ford meanwhile drove his race car from Sydney, complete with three passengers: one in the passenger seat and two more strapped into a box trailer in tow.

The race was contested on Australia Day, and typical of that time of year, it was incredibly hot.

Warm northerly winds fanned temperatures that were reported from the high 30s to early 40s—a true test of machine and man.

The airfield provided precious little shade for the spectators, and the crowd was estimated to be 17,000 – a Victorian record for the time, while the RAAF’s records noted an attendance of 40,000.

Interestingly, a 1947 story in The Age noted that the RAAF would receive most of the event’s gate takings, with another story indicating that a crowd of 100,000 was in the works.

All told, of the 26 starters, ten were classified at the chequered flag, with four drivers collapsing due to heat exhaustion.

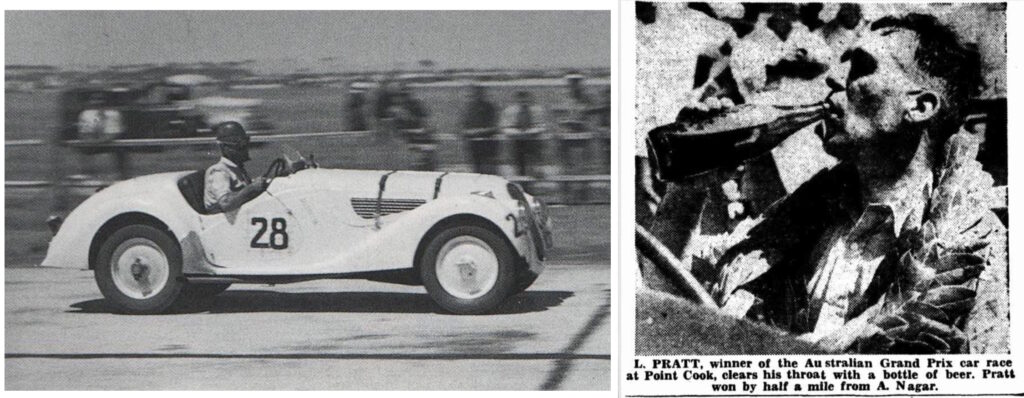

Run to a handicap format, the race had a surprising winner: New Zealand-born Frank Pratt, who won by nearly a minute in his aging 11-year-old BMW 328, taking home £1,000 from the total £1,500 prize pool.

It was a turn-up for the books in more ways than one, with Pratt still recovering from injuries suffered in an earlier motorcycle accident, a discipline of the sport where he was an accomplished competitor.

The car Pratt used was also relatively mildly tuned, and had been earlier involved in a fatal road accident that claimed the life of George Martin in 1938.

Oh, by the way, it was Pratt’s first-ever car race outside of a “semi-social” grass hillclimb near Geelong.

Perhaps the most interesting entry in the race, and maybe in the long history of the AGP, was Cec Warren’s Morgan, which kicked the race off with an 18min handicap.

Not only was the car the first and only three-wheeler to compete in the Grand Prix, but it was also the last ever entry to carry a riding mechanic.

The Age & The Herald – 26/27 February, 1948

True to the setting, the three-race program on race day featured flyovers between events from the resident squadrons, although the weather conditions prevented the helicopters from taking to the skies.

In fact, the Air Force infrastructure became a part of the proceedings: in the preliminaries, “Wild Bill” MacLachlan shunted into a truck parked near the circuit’s edge.

It is noted that the car nosedived over a ditch and rolled several times, fracturing his shoulder.

A story in the Truth newspaper in 1952 painted a picture of the wild streak of a “mild-mannered industrial chemist”.

Bathurst figured prominently in MacLachlan’s story—once, he tumbled down the hill three times in what was described as Bathurst’s “most spectacular smash.”

On another occasion, he crashed through a grove of fruit trees, while later, a collapsed wheel saw him teetering on the edge of falling off the top of The Mountain.

He also suffered a severe water skiing stack into a pile, while he twice suffered major shunts in gliders – once spinning into the ground from 1,000ft.

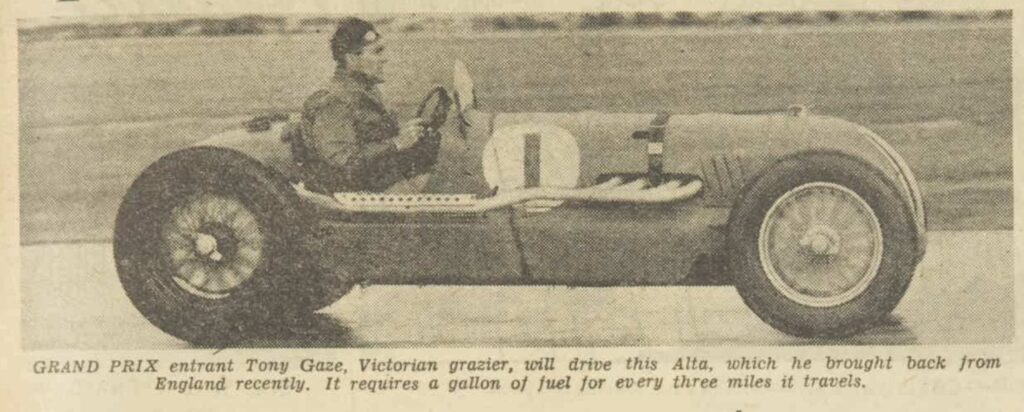

Plenty of big names or future stars participated in the race, including John Crouch, who won the following year in Leyburn, Alec Mildren, Bill Patterson, Doug Whiteford, Lex Davison, Tom Sulman, and Tony Gaze, the scratch marker for the race.

Gaze happened to be a WWII RAAF Squadron Leader who had previously landed on the strip where he raced. In the theatre of battle, he is credited with 12.5 confirmed victories—11 and three shared.

Ultimately, car racing would only ever make one appearance at Point Cook.

Motorsport would go on to utilise venues nearby, such as the old runways at Fishermans Bend from 1948 through 1960, while a circuit around Cherry Lake at Altona ran between 1954 and ’55.

Point Cook Today

While RAAF Base Point Cook’s utility has changed over the years, its important role in the history of our Defence Force has been its ultimate saviour—in 2004, it was added to the Commonwealth Heritage List, while in 2007, it was added to the National Heritage List and officially retained as a Defence asset.

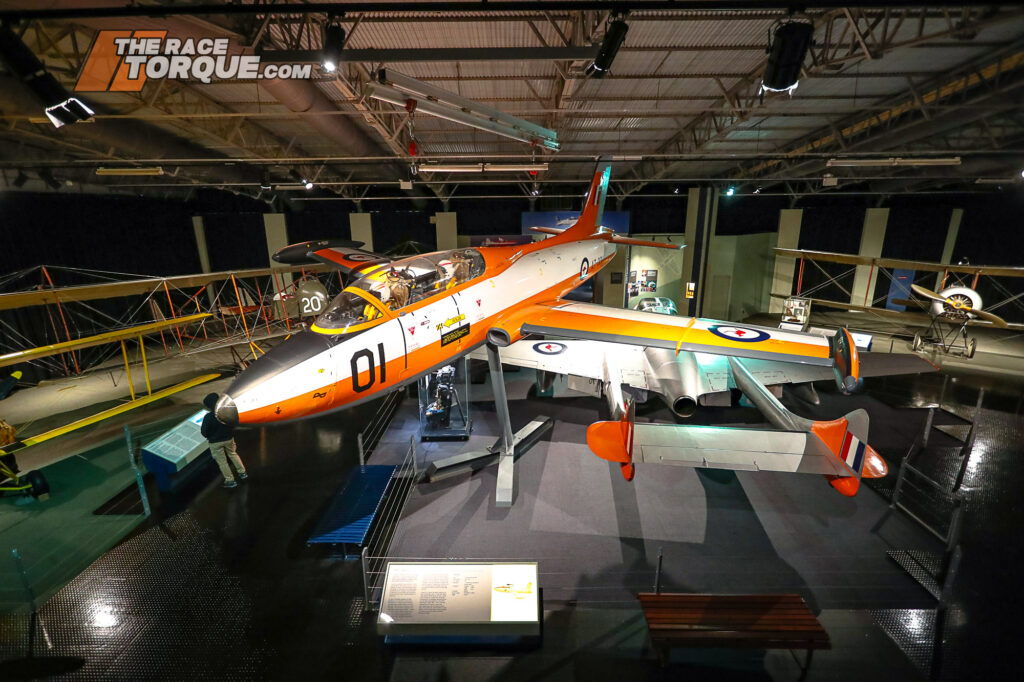

Today, the base is home to the City of Melbourne 21 Squadron, responsible for airfield base and base support, plus reserve training, and the 100 Squadron, the custodians of the Operation Historic Display Aircraft, which in recent years has been supplying the aerial entertainment at Albert Park’s F1 GPs.

The 1948 AGP has never been forgotten at Point Cook, with open days over the years recognizing the unique event.

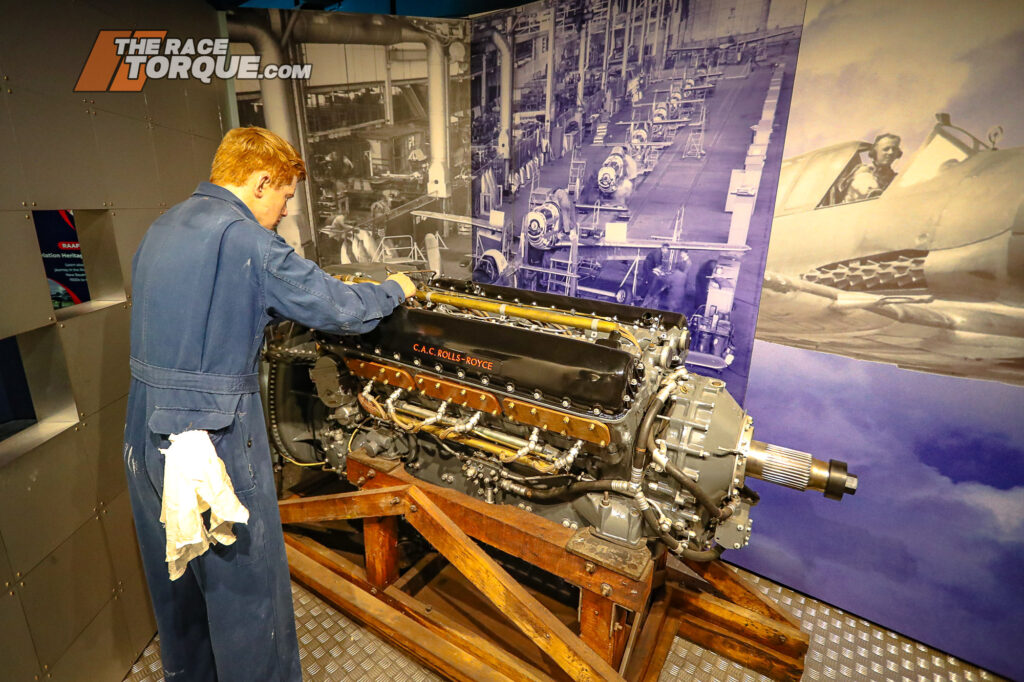

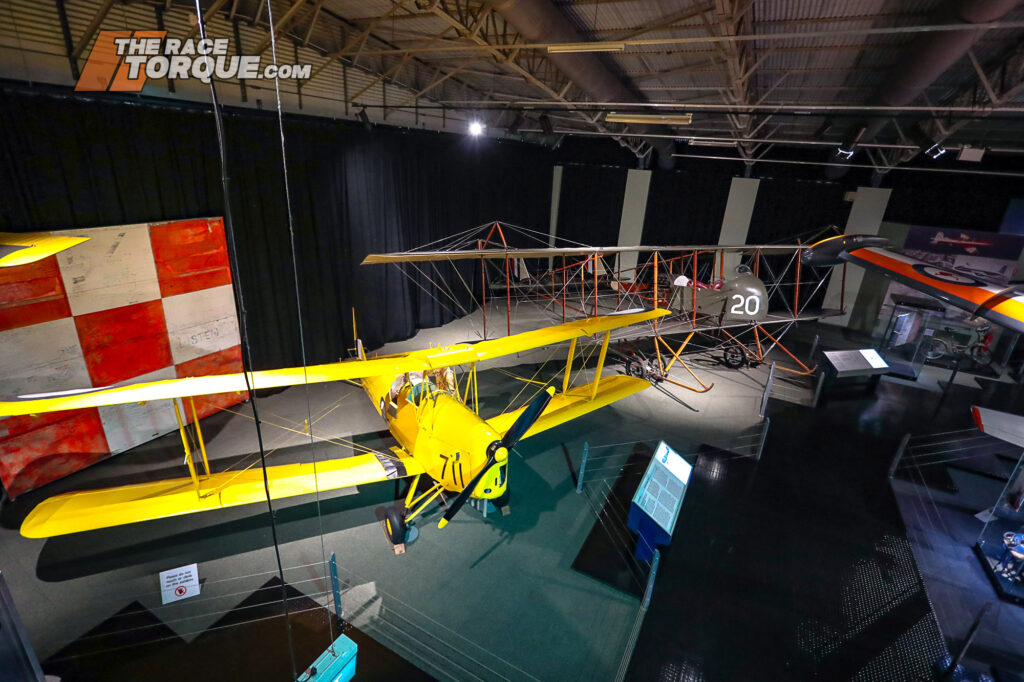

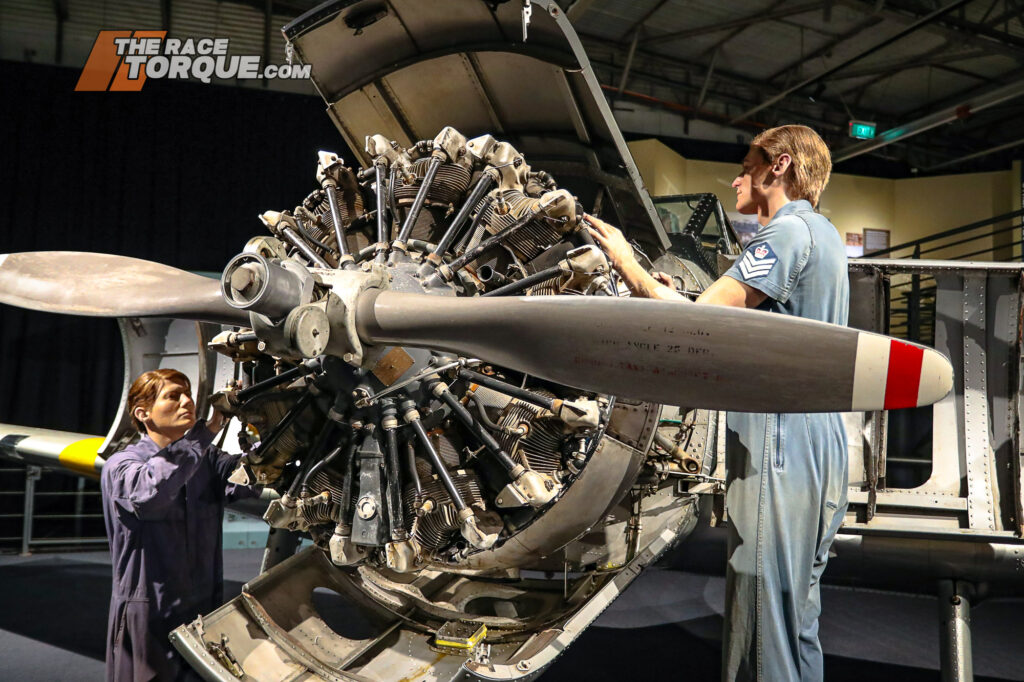

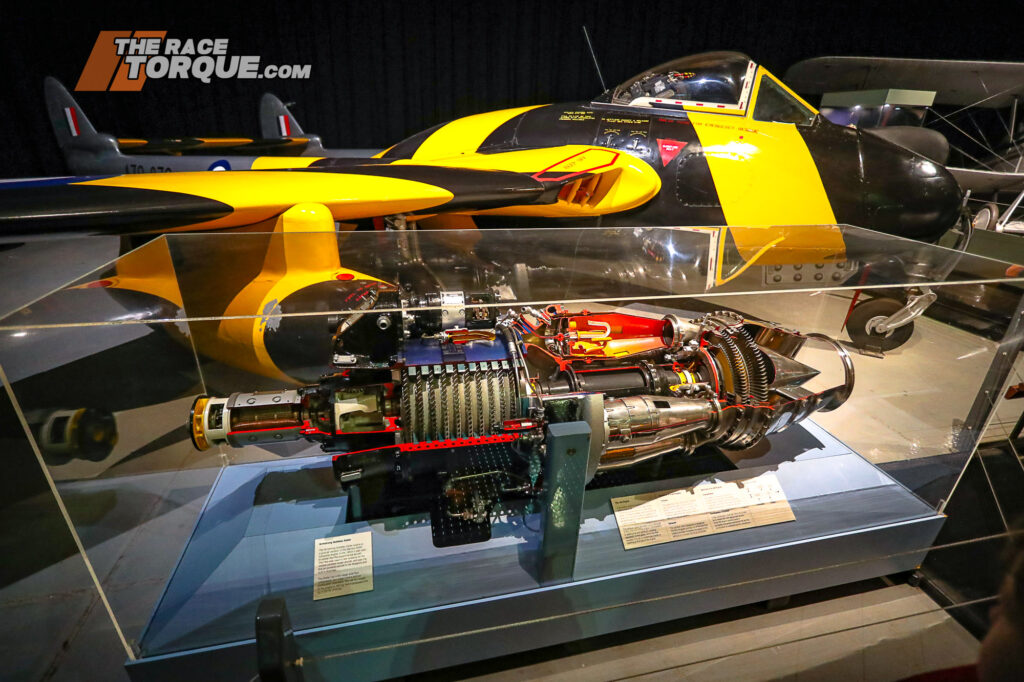

Also, since 1952, Point Cook has also been home to the RAAF Museum, which has recently undergone a significant renovation.

It’s a must-visit, even if you have a passing interest in aviating – the Museum tells the full story of the Air Force while also displaying many significant flying pieces.

Admission is free, but you need to book ahead.

The base remains home to WWI and WWII-spec buildings, including a pier and seaplane hangars.

Contributing photographer: Theo Walker