Mallala’s Missing Metres

LOOK AT MALLALA from above and there remains a faint outline of what is clearly abandoned race track. It’s a little known tale that the 2.6km circuit North of Adelaide was actually once much longer than it is these days. So, what happened? Why was it shortened? This is the story of Mallala’s missing metres..

FEW AUSTRALIAN circuits have remained untouched from when they first opened their pavement to cars or bikes and competitive motorsport.

Fly around the various racing circuits in Australia and you’ll not find many that retain an identical layout to what they started with.

Mount Panorama has retained much of its originality, but the addition of The Chase in the lower third of Conrod Straight was a dramatic departure from what was there before, plus the many safety improvements have definitely changed the nature of the place, if not the challenge.

Phillip Island lost several hundred meters at the corner currently known as Honda and while the original Winton layout remains pretty much as it was, the circuit copped a lengthy extension two decades ago that basically means the short circuit is rarely used.

Sandown was heavily revised in the 1980s – though to be fair its not changed much since.

Of the current national-level circuits used regularly, it’s probably only Wanneroo in the West, Baskerville and Symmons Plains in Tasmania, Lakeside in Queensland and Mallala Motorsport Park in South Australia that remain the old-school circuits where you could use an original track map and not be led astray.

Except, Mallala has changed since it was founded in 1961 – and changed quite significantly.

This is the story of Mallala’s missing metres.

MALLALA was sold to a company called the Brooklyn Speedway Co. in 1961 as the Royal Australian Airforce divested themselves of assets obtained and created throughout the war.

You can read about Mallala’s history as an RAAF training base during and after the conflict in a previous TRT yarn here.

The Brooklyn Speedway Co. had promoted racing at the former Port Wakefield circuit, however the short track in the Mallee was deemed too short to be used for the Australian Grand Prix, which required a circuit to be at least two miles (3.2km) long.

With South Australia due to host the then-rotational Australian Grand Prix in 1961 an alternative was needed and it was at Mallala where the existing taxiways and aprons of the RAAF airfield offered the perfect solution.

With the land purchased in the first half of the year, the promoters quickly set about clearing the site to make it suitable for motorsport, including bringing all of Port Wakefield’s infrastructure to the venue and using some of the inherited RAAF assets as well.

Despite the quick turnaround, On August 19, 1961 Lex Davison won the Australian Grand Prix aboard his Cooper Climax: Bib Stilwell and David McKay completing the podium. 15,000 spectators watched the race unfold.

Thus the start of the longest chapter in South Australia’s motorsport heritage had begun. Mallala was a thing.

PHOTO: Courtesy Mallala Motorsport Park

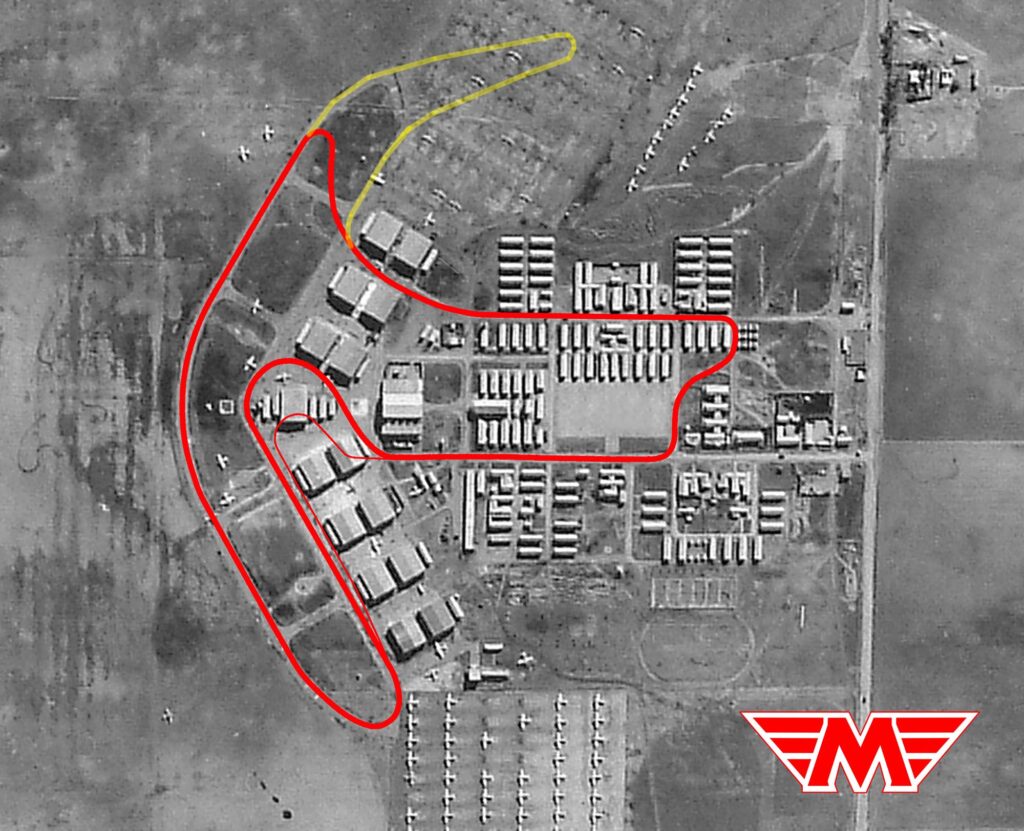

THE MALLALA circuit used for the Australian Grand Prix, and for subsequent Australian Drivers’ Championship and Australian Tourist trophy events held between 1961 and 1964, was much like it appears today but for one critical change.

It was longer.

800 metres longer, in fact.

A lap of the-then nearly 3.4km circuit started at the same place as it does today, with Turns one, two, three and four almost identical as they appear today.

It was as the field run up the back ‘straight’ where things became different.

Where today the tight, technical Northern Hairpin offers a key overtaking opportunity the original layout didn’t feature the slow right-hander, instead a second high-speed right-hand kink, with turn-in point approximately at the point where the deep gravel / sand trap commences now.

This second sweeper then pointed cars to the East and into a heavy braking zone into a hairpin bend that appears just as tight – if not tighter – than today’s Northern hairpin is. ‘

From there the field accelerated out onto another straight, the road gently curving to the left before a braking zone slowed cars some 400m later for a left-hand corner – that would have proven another overtaking opportunity – approximately half-way along what is now the turn six sweeper.

The remainder of the lap continued as is; braking hard into the turn 7 hairpin, the left-right through the Esses and Clubhouse and then back along the start-straight again.

There is no argument that the extra 0.5 of a mile, or 800m made Mallala Motorsport Park a very different style of circuit than it is today.

While the stop-go nature of three straights linked by three harpins was essentially the same, the speed potential on it was significantly higher.

PHOTO: Richard Craill

THESE DAYS the fastest cars that race at Mallala brake from approximately 250-260km/hr for the Northern Hairpin.

But instead of braking, the old circuit would have seen competitors remain flat to the boards for a second-right hand sweeper that would have been significantly quicker than the first in Mallala’s Straight-that-definitely-isnt-a-straight.

These days it would be a fearsome 260 km/hr kink similar to something you’d see at Phillip Island and not out in the flat, flat lands of South Australia’s inner North pastoral lands.

The subsequent braking for the ‘old Northern’ hairpin would have been a much bigger stop yet would still be a sensational overtaking opportunity.

The corner that linked the older circuit with what remains now would have also been interesting – a quickish approach into a decent stop into a left-hand corner, rare for Mallala which leans predominantly right.. at least in terms of direction of travel.

It would have made a lap of Mallala quite different to what it is today.

PHOTO: Courtesy Mallala Motorsport Park

SO, why was the circuit shortened like it was in 1964?

TRT has researched Mallala’s lost 800m and while there’s no definitive answer, there are several stories that help explain the decision to tighten the track to it’s current 2.6km layout, one that has remained almost untouched since the ‘60s.

The best and perhaps the most reasonable answer is that the track surface North of where the current Hairpin sits was degrading and no longer fit for purpose.

Remember, Mallala was literally crafted from the layout of the existing taxiways, hardstand areas and access roads that were already there, hangovers from its time as an RAAF base.

Activity at the base became less and less vigorous throughout the 1950s as the Air Force consolidated their assets at the Edinburgh base closer to the city, with upkeep diminishing at a similar pace.

With a group of locals purchasing the airfield in a bid to ensure the 1961 Australian Grand Prix was successfully staged, which it was, there was limited time to prepare the circuit before the race weekend – little more than six months, in fact.

It’s clear that once the circuit had a few years to settle into regular operations some sections were in better condition than the others and, with budgets tight, there was possibly little appetite to resurface.

Thus, a short link was created linking the existing circuit together between the back straight and the existing sweeper to create what we now know as the Northern Hairpin.

Furthermore, and perhaps just as critically, the existing circuit had done its job and successfully hosted the Grand Prix – probably for the only time.

While the mandate that stipulated that the any circuit hosting the AGP had to be longer than two miles remained in force, the actual chances of Mallala hosting the event again were ever diminishing.

To that point, CAMS (now Motorsport Australia) ran the AGP on a rotational basis, shifting from state to state in a bid to fairly share the spoils of what was at the time the biggest race in the country.

However, at a meeting of the CAMS National Control Council just a month following Mallala’s Grand Prix, a majority of state representatives voted to scrap the rotational policy, replacing it instead with a process of awarding the GP to promoters ‘willing and able to organise the event to the required standards’.

In yet another case of the Eastern seaboard states dominating the national conversation, only South Australia and West Australia voted against a motion that would almost certainly gift the race to the cashed-up promoters in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria for the foreseeable future. The smaller states had little chance to compete.

Following the 1962 AGP held at Caversham, an event already locked in prior to the fateful CAMS decision, no circuit outside the three East Coast Powerhouse states would host the race again until it returned to Wanneroo in 1979.

This change in policy almost immediately ruled the Mallala promoters out of any chance of returning the Grand Prix to South Australia, so as well as being costly in upkeep or potential repair, Mallala’s extra 800 meters weren’t really needed anyway.

The Australian Grand Prix would not return to South Australia until 1985.

MALLALA’S missing 800-odd metres offers a fascinating ‘what if’ moment of reflection when you visit the circuit.

The old tarmac remains visible, broken in places and overgrown in others, north of the hairpin. It’s easy to trace the exact layout too; noting the width of the circuit, the braking zone to the hairpin and the point at which it returned towards the existing circuit (at a point now covered by the large spectator hill on the exist of the current hairpin).

Little has been written or discussed about the longer version of South Australia’s longest-serving permanent race circuit, probably because it only existed for three of the venue’s more than now 60-year history.

Yet it remains a fascinating chapter in what is a classic, old-school Aussie circuit that under the current ownership of the Shahin family, continues to offer plenty to the local motorsport scene – and with the potential of more to come.

In yet another case of the Eastern seaboard states dominating the national conversation, only South Australia and West Australia voted against a motion that would almost certainly gift the race to the cashed-up promoters in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria for the foreseeable future.