The Bathurst Riots: The BYOG Ban

The events on top of the hill, especially in 1983 and ’85, placed a spotlight on the Easter motorcycle races.

Calls to cancel the meet were met by resistance from the local Bathurst Chamber of Commerce, it was a big money spinner for the town, but the bloodshed couldn’t continue without there being major changes made.

However, something radical indeed shifted the needle.

Further Reading:

Part 1 – The Bathurst Riots: A History of Conflict

Part 2 – The Bathurst Riots: The 1980s War

The Ban

By mid-August 1985, life on top of The Mountain changed forever, with NSW Police Chief Superintendent Don Freudenstein announcing a widespread ban on bring your own grog, alcohol and flammable liquids onto the venue at race meetings, after consultation between senior police, the Bathurst City Council and other interested parties.

“The meetings will be policed on the same basis as any public place, and the person offending will be dealt with in exactly the same manner as they would be if they offended on a public street. Police will not make any allowances when dealing with breaches of the peace,” he said.

It was noted that in the past, utes or small trucks packed with alcohol entered the venue, with one individual later noting they won a bet by transporting ten slabs into the track on a motorcycle.

Elsewhere, some are noted as bringing bulk petrol into the track.

The council and police would conduct searches, and restricted quantities of alcohol would be available from authorised outlets on top of the hill, with sales limited to beer and a limit of two open cans per person per buy.

‘Dry’ areas were also installed along the outside of Hell Corner and at Sulman Park, an enclosure that stood for many years to follow.

The first event to be held under the new rules was the 1985 Bathurst 1000, a situation that didn’t impress the campers. They lost not only their beloved Group C touring cars but also their booze, and the event was seen as a test run before Easter ’86.

Interestingly, while one vice was on the outer, another was in: this was the first Bathurst race to allow gambling at the TAB, with a temporary facility set up at the circuit for those looking to have a punt.

While at the 1000, the boys would be boys, and there would be an element of madness in the bullring, however, unlike the bike meets, there were never bloody riots breaking out.

That said, crowd behaviour at the touring car meet continued to be under the spotlight until the early 2000s, when genuine crackdowns weeded out the last of the bad eggs.

And besides, where there is a will, there is a way, and smuggling booze into the campground became a sport – it spawned the legend of buried beer on top of the hill, with industrious campers literally digging deep to ensure their supply come race weekend.

Subsequently, one of the smallest crowds on record was on hand in 1985 to witness John Goss bring the big Jaguar home first in the James Hardie.

Come early 1986, unrest was predicted at Easter, with visitors upset with the bans, while some quarters pointed to a probable boycott because of the sanctions.

The Motorcycle Riders’ Association called on its members to stay at home, aside from anything – “You have large groups of police intimidating campers by walking into campsites and searching tents without reason.”

The event was well and truly under the microscope, with the police minister noting he would attend to get a feel for the festivities. He noted that it was an incredibly expensive event to police, and if it continued along its old trajectory, he would withdraw his support.

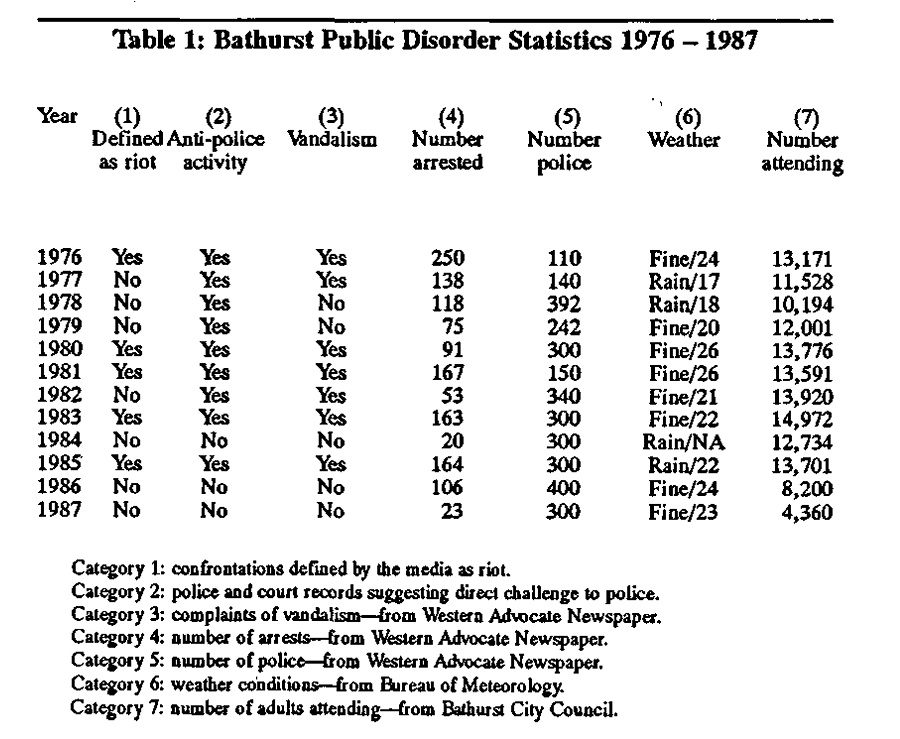

Come race weekend, the authorities weren’t mucking around, with 400 officers imported for the event, with the end result being only a handful of arrests – there weren’t enough punters there to carry out a riot, with crowd numbers down by two-thirds.

A warning to patrons from 1987

The same happened in 1987, the final meeting to be held on the original Mount Panorama layout, with only 23 people charged on 45 offences, mostly traffic-related.

The changes to the event saw the hooligans stay away, ditto the true race fans.

The end of the line for the Easter Australian Motorcycle Grand Prix at Bathurst came in 1988 with a Mick Doohan victory – the 1989 meeting was slated to switch to November, but that was cancelled in the new year.

Safety was an ongoing issue, while the addition of the 500cc and World Superbike visits Downunder diluted interest in Bathurst, with sponsorship dollars flowing in that direction.

One suggestion was to implement a motorcycle-friendly short circuit on the infield behind the pits—the concept floated around for some time, however, a permanent facility there wouldn’t be palatable from a noise perspective for citizens of the growing city.

By 1991, the police compound had been dismantled, with the building repurposed as a first aid hub.

The bikes and sidecars returned to support the Bathurst 12 Hour from 1992 to ’94. The 1992 event reported 4,500 bikes through the spectator gates, no booze bans, a low police presence, and no-nonsense from the crowd.

With the 12 Hour moving to Eastern Creek in 1995, one final Easter revival came in 2000, however, that concluded with the promoters filing for administration, bringing to an end 62 years of two-wheeled racing on The Mountain.

Subsequently, the camping facilities on top of the hill have improved markedly.

Policing the Bathurst Motorcycle Races

A somewhat polarising report for the Criminology Research Council made some interesting observations about the ongoing battles at Bathurst, considering various inputs from police, outlaw gangs, recreational motorcycling groups, the local council and more.

Entitled ‘Policing the Bathurst Motorcycle Races’, as compiled by Dr Arthur Veno, Elizabeth Veno and Rudi Grassecker, it cast a fascinating light on the mechanisms behind the conflicts.

The study kicked off with a comprehensive survey of motorcyclists at various events around the country. It concluded that bikers seem to be spread across demographic variables such as class, the negative stereotype of the bike rider depicted in the mass media seemed inaccurate, and the NSW police were particularly problematic with bikers from Southeastern Australia.

Next, the study looked at the various policing tactics employed at different events, such as the Genoa Bike Rally, The Wombat Rally, The Sydney Bike Show, the Hundredth Anniversary of Motorcycling Rally held at Phillip Island, and Broadford, with considerations such as attendance, alcohol policy, police profile, arrests, rowdiness, incidents, injuries, fights and more considered.

From this, it became apparent that high visibility policing resulted in higher anti-police sentiment, reduced crowd enjoyment levels, lower attendance figures, and lower profit for event organisers.

Also, no alcohol restrictions resulted in higher rowdiness, while self-policing appeared to be the most effective form of crowd control, with peer pressure playing a role.

Moving onto Bathurst, the researchers planned a ‘Search Conference’, whereby all of the participants would sit around a table to come to a solution – the police didn’t reply, while the Press Council of Australia flagged they may have attended if the Bathurst City Council and the Motorcycle Riders Association dropped charges against select media members.

Outside of the research, the parties were brought together without police involvement, where it was suggested that privatisation of security was the way forward.

When it came time to observe the events on top of the hill, it was noted that the presence of the police compound dating back to the 1970s saw the violence become institutionalised and exaggerated.

Propositions to be tested included if weather conditions affected the likelihood of violence, if the bikers/spectators or the police caused the provocation, sensationalism by the media, if a lack of entertainment contributed to the mess and more.

Away from the realm of Bathurst racing, there was an ongoing conflict between police and the youth, while at the same time, the bikers were a logical minority group for the media to leverage in creating public hysteria – the deviance of bikers was easy to amplify.

The report noted that the media was guilty of inflaming the situation.

After the 1985 riots, it was reported that there appeared to be a correlation between warm weather, increased alcohol consumption, and elevated rowdiness. Similarly, it was noted that compared to surveys at other motorcycle events, the Easter crowd held greater anti-police sentiments, had been in more previous trouble with the police, and was younger than the general bike-riding population.

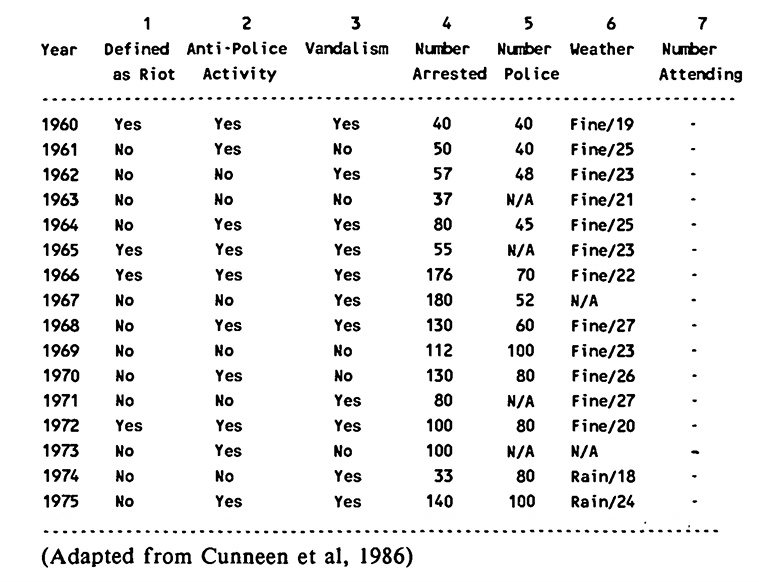

Statistics compiled in the Situational Prevention of Public Disorder at the Australian Motorcycle Grand Prix Report

The Decline of the Bathurst Motorcycle Races

Two parties were identified as profiting from the Easter conflicts: the police, who used the events as a bargaining chip for further equipment support, such as water cannons, and as a training ground, while the media gained from its extensive television coverage and newspaper sales.

A motorcycle rally at the Phillip Island Grand Prix Circuit over New Year in 1986 was shown as a blueprint for how police deployment could be improved, featuring:

1) A large police presence, but outwardly friendly, mingling with the crowds

2) Local, older and country-experienced officers

3) Tolerance towards petty issues

4) Hidden backup reserves

5) The sale of non-bottled alcohol, limiting missiles

6) Standard closing times of liquor outlets

7) Organised entertainment

Although these ploys combined to lower attendance at the event, police visibility was also noted as an issue.

At Bathurst, police mingling was employed in 1984 and ’85, although the final riot of ’85 suggested that that tactic alone would not quell issues.

The issue at Bathurst was the institutionalised nature of the violence – even when the policing task was offered to other bodies, such as the Motorcycle Riders’ Association or the Hells Angels, neither wanted to touch the problem.

With the booze ban in place for Bathurst 1986, the Bathurst City Council and the police were charged with searching attendees, a ploy which may have worked had the police attendance not been its largest on record.

It was also noted that the police compound had increased to six times its original size.

Ultimately, the changes in ’86 resulted in attendance being down 40 per cent, with businesses in Bathurst feeling the pinch.

The report made several recommendations to stem violence on top of The Mountain, with the first being a central person in charge of controlling the event, outside of the police, as appointed by the various interests in the event.

Next, the police HQ should have been moved away from its base at McPhillamy Park, with the existing compound to be converted for community use, such as first aid or as a food outlet.

From a policing standpoint, a community model would better integrate their presence, much in the same way as the Phillip Island event was policed, including the use of motorcycle/mounted officers, no visible guns, giving people the opportunity to self-test before they attempt to leave The Mountain, significantly decrease the interference of travellers en route to the event, increase the visibility of council workers, and locate backup officers away from camp areas.

Alcohol consumption also came under the spotlight, with a slight loosening of the ban.

Also, it was suggested that bottle shop sales in the Bathurst area should concentrate on non-glass bottle sales, and that plastic bottles be made available at the gate to avoid contraband being confiscated.

As per 1986, council workers should continue their searches at the gate, with restrictions on firearms, hard drugs, cans of petrol, and glass containers.

Entertainment came under the spotlight.

In 1982 and ’83, rock bands played in the quarry at The Cutting with mixed success. The report suggested:

1) Small-scale concerts with local bands

2) Outdoor movies with bike-orientated films or racing clips

3) If the police compound were to be removed, place the entertainment there as a central focal point

4) Provide a safe area for the bullring to take place

5) Formalise the gymkhana aspect of festivities with a designated motorcycle group to be in charge

Ultimately, after five years of ongoing studies into the conflicts at Bathurst, Dr Veno addressed a rally to call on the New South Wales Nick Greiner Government to honour its pre-election promise to review policing at the events.

He suggested that motorcyclists be responsible for policing the event and that large numbers of police incite violence, points refuted by the police.

Later, in 2002, Veno launched a book entitled The Brotherhoods: Inside the Outlaw Motorcycle Clubs, which analysed the culture behind the movement.

A later report entitled ‘Situational Prevention of Public Disorder at the Australian Motorcycle Grand Prix’ by Veno and Veno noted that self-policing overseas at motorcycle events with outside marshals provided a trouble-free environment.

The report set about learning from Bathurst’s mistakes as the Australian Grand Prix moved to Phillip Island in 1989 and became a round of the World Championship.

Policing style was core, alongside positioning the event as being family-friendly with better facilities and entertainment.

The traffic plan was looked at, with the Grand Prix Rally seeing patrons travel in convoy from Melbourne, all with police cooperation on multiple fronts, including closing off intersections en route to ensure smooth passage for the 100km journey.

At the Island, the five separate camping areas were privately run, with the operators assuming control of the policing in their plot with marshals.

From a media perspective, a range of tactics were employed to ensure that the event was broadcast in a favourable light.

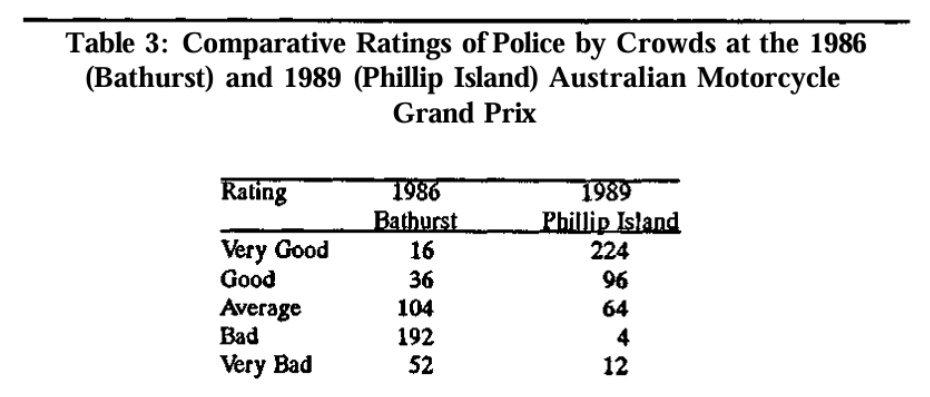

The work was successful; of the 240,999 attendees at the 1989 Australian GP at the Island, only 36 were arrested, and police sentiment was much higher than in Bathurst, below.