THE ULTIMATE UNDERDOG: AARON MCGILL

“THERE were no spoons, let alone silver ones!”

WORDS & IMAGES: Mark Walker

Money makes the motorsport world go around; no matter how someone has found their way onto the starting grid, somebody has had to pay for it.

From self-funded drivers, to those with a wealthy benefactor, many at the elite end of the sport are there because of sponsorship.

For Aaron McGill, his 39 years in the sport has largely been achieved through the graft of chasing sponsors, doing things his way, and ultimately on a budget.

Taking the road less travelled has endeared him to followers, with the love of the sport taking him from Formula Vee to Suzuki Swifts, Super Touring, the Development Series and TCM.

Talking to The Race Torque, one of the sport’s ultimate underdog’s reveals some classic tales from the journey so far, as well as his brush with the bushfires early this year, which saw him jump behind the wheel of his truck for the rebuilding mission.

Money’s Too Tight to Mention

“I remember one-time Paul Morris came by, he walked past as we were tinkering around with brakes, this was before race one,” said McGill of a Development Series race weekend.

“I pulled out these pads that were basically metal, Paul said “What are you doing with them?” Basically the conversation went that I explained these are what we are using, “For God’s sake, you’re going to kill yourself”… a couple of cartons of Corona swapped hands, and I wound up with a decent set of brake pads!

“Money was always tight, there was that one year, I think it was ’07 when we landed the HPM deal, that was quite ironic, there was more money, but all of a sudden I become very popular with everybody, that by the end of the year I became more broke than ever.”

Learning to Sell

“I joined AMP way back to learn how to sell, I didn’t know how to sell anything, I thought that selling insurance was a hard task, and that’s where I learned the telephone technique,” said McGill.

“If I have to make 100 phone calls, and get told to piss off for 99 of them… you wind up with a formula, if I put in this much work, I will get this many opportunities, and out of that I might get one a month that says yes.

“You can’t have a normal job and make three phone calls a week and expect to land a sponsor – you might get lucky, but when you’re chasing a quarter of a million dollars, when you’re a privateer on a shoestring, and you have to put the money together, you had to do the work.

“That was always the problem, a lot of people didn’t think I had a right to be there, some years were harder than others.

“I suppose with driving semis (Aaron can now be found driving trucks for a living), if you have a customer who says “I’m in, I need half a truck full of stuff taken to Brisbane”, whether you have the truck full of freight or not, you have to go.

“That’s what happened with the racing, sometimes you would roll up to Clipsal with spaces all over the vehicle, and you just didn’t have the opportunity to put the rest of the package together – you just knew you were screwed.

“I can remember one year in Adelaide sitting out practice sessions, so we would have enough money for fuel and tyres, and I had to throw everything at doing three laps in qualifying to get on the grid. Not ideal…”

To chase the motorsport dream, McGill had to leave his career in the real world, to give himself the flexibility to chase sponsors, and spend time commuting to the racetrack.

“I got a job with Ian Luff at his driver training school – it gave you the choice of having two to three big hard days a week, in the sun in summer and freezing your backside off in winter at a skid pan or a racetrack, blowing whistles and waving flags. But it did give you the opportunity on your days off to go racing.”

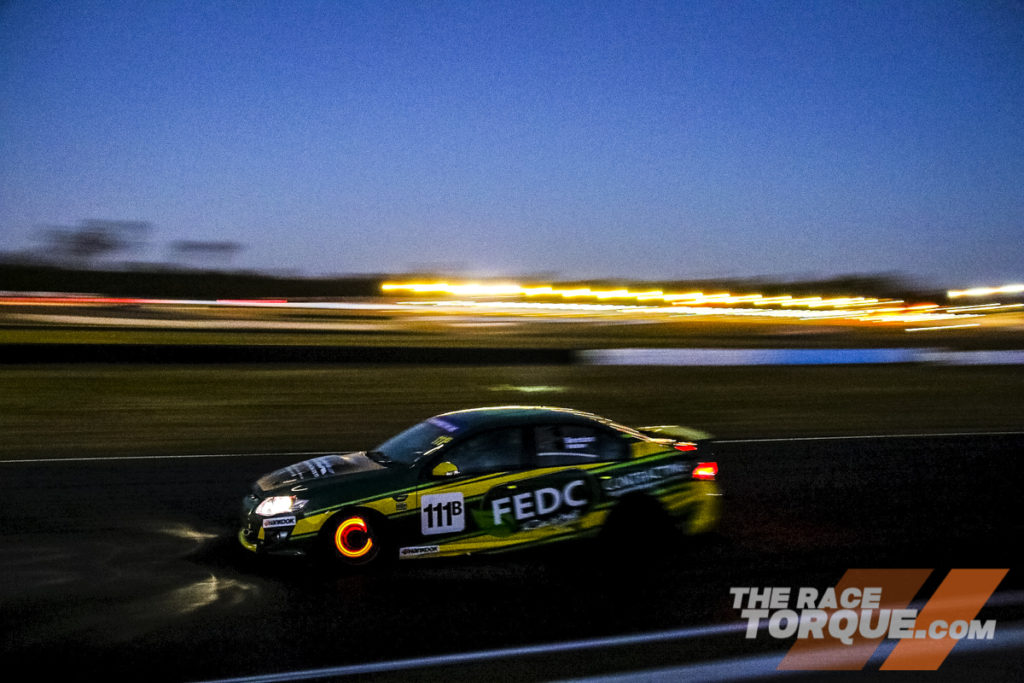

Creating a Fight in the Night

Away from his own driving, McGill spent a period as the category manager for CAMS Production Car racing, a difficult task when faced with the prospect of dealing with the various stakeholders, from state level categories to AASA aligned racers.

“It was like trying to herd cats on cracker night, with all of the parties having their own opinions on how it was going to run,” said McGill.

“Probably one of my greatest achievements that nobody knows about was putting together the Fight in the Night at Queensland Raceway. That was mammoth, because when I went to Paul Taylor (at CAMS) and said that I wanted to run a night race, you can imagine the look I got… that wound up going all the way to the FIA in France to approve it.

“It wasn’t just (John) Tetley and CAMS, it was how are you going to light it, the distance between the lights, the lights had to be a certain level, it was massive.

“It didn’t make any money, again, but it gave production cars a bit of a footing that has got them to where they are now, with the Six Hour at Mount Panorama… it’s grown, and I’d like to think I’ve had a bit of a hand in that game to get it where it is.”

Helping Hand

A family camping holiday to Milton on the New South Wales south coast post-Christmas brought McGill face-to-face with the realities of the devastating bushfires which ultimately decimated the area. Fortunately, they were able to escape before the inferno struck around New Year’s Eve.

“I just felt helpless sitting at home, watching all this unfold. That led me to ask what can I do?” Asked McGill.

“I approached Convoy Missions Australia as they had just kicked off, and there was no convoy, I was it! They had a lot of donations from the Bondi Surf Club, so I loaded that up, and headed to Batemans Bay.

“I was quite moved when I got there … it was chaos, I could imagine a war being just like that, everyone had the wherewithal to swing in and solve the problem, but there was the logistics nightmare of who was in charge, and where do you go?

“A chopper had gone down into a dam there and contaminated the water supply. When I pulled the curtain back on the trailer and the locals could see it was all 600ml bottled water, there was just applause… I thought, my God, these people are really up against it.”

Taking on the challenge, McGill by default became the designated logistics manager for the operation, with him personally leading trucks on eight trips to the disaster zone, with the transport equation growing into a bigger recovery effort.

“I met a guy down there on his farm, and we helped him rebuild at Cobargo,” said McGill.

“He had no fences; it was a mess. So, I rounded up about 25 of us, and we went down there for a weekend, chopped trees up and helped him get back on his feet… he was one of hundreds, it was an unbelievable situation, it just put everything in perspective.”